Although the hype surrounding the recent launch of the TurkStream pipeline and the in-progress Nord Stream 2 would have readers believe otherwise, Russian energy dominance in Europe is nothing new. In 2018, the European Commission stated that the EU imported half of all its consumed energy. That dependency is particularly high for crude oil and natural gas.

Currently, Russia holds a third of Europe’s gas imports and imports 140 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas annually through Ukrainian pipelines. The two most important reasons for Russia’s gas monopoly are economical and practical: distance and cost. Geographic proximity makes Russian gas not only more reliable than other competitors but also cheaper and closer.

Why Build Nord Stream 2 and TurkStream?

The pre-existing monopoly begs the question of why build two new pipelines, both of which have attracted ardent criticism from the United States and certain European countries. Many critics claim, for example, that Russia has the potential to exploit that energy dominance for political gain. Others argue that Nord Stream 2 would supply gas to Germany first, effectively removing other EU nations from the decision-making process and exacerbate inter-EU tensions.

However, building two new pipelines broadly serves Russian interests. Both projects not only cement Russia’s monopoly on gas but also open the door towards Russian gas exports reaching China as well as seize a share of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) market. Nord Stream 2 mainly helps Russia export gas to the northern European market and bypass Ukraine and the corresponding political situation there. TurkStream also plays a role in circumventing Ukraine, carrying gas to south and southern Europe and Turkey.

To answer critics’ concerns about energy security, many European politicians point to proposed legislation that aims to prevent Russian market manipulation, long-term goals to address the security of supply challenges, and diversification away from fossil fuels. The Third Energy Package, for example, aims to liberalize and integrate natural gas markets—ultimately aiming to break up the Russian-state own monopoly (i.e., Gazprom and Rosneft).

The EU’s Energy Union strategy further commits to ensuring that every EU state has access to at least three different sources of gas. Additionally, many EU states are moving away from fossil fuels. Some Baltic states, for example, are developing LNG terminals (ex: the Klaipeda LNG terminal) to diversify their gas imports and supporting low-carbon energy sources.

Despite these attempts to become more energy-dependent, Europe truly does not have a leg to stand on. Up until 2030, Russian pipeline gas and global LNG will remain the two main sources of gas for the EU. Further, no significant pipeline gas that does not already originate in Russia will be available in the EU before 2025.

TurkStream

After the cancellation of Russia’s South Stream project in 2014, Russia quickly moved to replace one pipeline project with another. The South Stream project was led by Gazprom and aimed to transport Russian gas across the Black Sea to Bulgaria and, from there, disperse within Europe. However, in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and subsequent invasion of Eastern Ukraine, along with a regulatory dispute between Gazprom and the EU, the project was canceled.

In response, Gazprom signed a Memorandum of Understanding with BOTAS Petroleum Pipeline Corporation (Turkish state-owned gas company) to construct TurkStream in December 2014. In 2019, TurkStream was officially completed and on January 8, 2020, Russian President Putin and Turkish President Erdogan inaugurated TurkStream and certified it ready for use.

Nord Stream 2

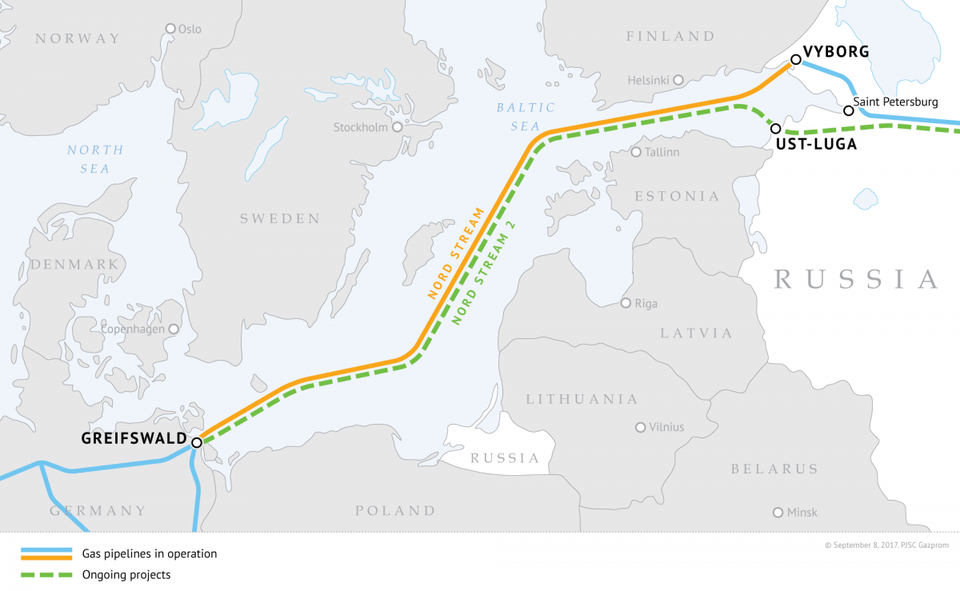

In 2012, after the successful construction of the initial Nord Stream pipeline, Gazprom also moved to expand to additional lines (later named Nord Stream 2). In 2015, Gazprom signed an agreement with Royal Dutch Shell, E.On, OMV, and Engie to build Nord Stream 2. Poland blocked this plan in 2017—leading Gazprom to develop a financing plan with Wintershall, Engie, OMV, Royal Dutch Shell, and Uniper instead.

In 2018, Germany approved Nord Stream 2’s construction permits in German waters. Although the U.S. has threatened sanctions on companies that work with Gazprom—causing Allseas to pull its support—Gazprom has claimed that it would complete construction alone and would finish by 2020.

Many observers note that TurkStream is likely a counter to the original U.S. backed Southern Gas project, which was developing a pipeline from Azerbaijan to Europe and that Nord Stream 2 is a bid to replace Ukraine as a transit state. Not surprisingly, members of the U.S. government have expressed concern over TurkStream and Nord Stream 2—claiming that it threatens European energy independence and security.

Many Central and Eastern European states see the pipeline as an attempt to undermine European unity and bypass transit states such as Poland and Ukraine—also depriving those countries of transit fees. However, Germany has argued that the pipeline was purely market-driven. In response to threatened U.S. sanctions, Germany warned the U.S. to “mind its own business.”

Together, TurkStream and Nord Stream 2 provide Russia with over 140 bcm in capacity—amounting to almost the same as Ukraine’s total transit capacity. TurkStream not only provides Russia with a stronger monopoly on gas in southern and southeastern Europe but also strengthens an already-strong Turkish-Russian relationship. Given the financial incentives to be Europe’s new gas hub, it is no wonder that Nord Stream 2 has also led to a stronger German-Russian relationship.

Russia’s Energy Dominance: Reinforced

The construction of TurkStream and Nord Stream 2 reinforce Russia’s dominance of the energy market, even though it may not lead to the political leverage that many critics expect. With one pipeline already completed and another expected in 2020, both TurkStream and Nord Stream 2 illustrate Russia solidifying its grip on the European market while also expanding its reach to other markets. This monopoly on gas is strengthened by Europe’s gas market—where demand is only growing.

In 2019, Europe imported 123 bcm of gas last year, nearly twice as much as 2017. Further, critics who point to energy security and independence, such as the U.S. do not affect policy in practice. While sanctions against working with Gazprom have somewhat of an effect in cooling interest, in this case, economic interests trump security interests. Russia’s geographic proximity to Europe means that Russian gas will be closer and cheaper than other competitors for the foreseeable future.

However, while Europe’s gas markets may be inherently dependent on Russian gas, Russia is similarly reliant on the European market as a buyer for its gas. In short, Europe is Russia’s most important market for Russian natural gas exports. This limits Russia’s ability to manipulate energy politically without severely compromising its economic relations with Europe. Therefore, Russian renewed energy dominance in Europe is certainly on the horizon with the imminent arrival of Nord Stream 2 and preexisting TurkStream. However, it is not nearly as concerning as Russophobic critics would have the public believe.

About the Author

Gabriella Gricius is a Ph.D. student in Political Science at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, CO focusing on Russian studies, Arctic politics, and critical security theory. She also works with Dr. Wilfred Greaves at the North American and Arctic Defense and Security Network (NAADSN), focusing on human security. She is also fluent in German and Dutch and reads Russian on an intermediate level. She is also a freelance journalist and writes for a variety of online publications including Foreign Policy, Global Security Review, and Riddle Russia, amongst others.