From rubies in Mozambique to emeralds in Zambia, opals in Australia, and Jade in Myanmar, the mining industry is undergoing an extraction renaissance that is as profitable as it is contentious. While concerns over environmental degradation, population displacement, employment of slave and child labor contribute to the fracturing of communities and exacerbate internal rifts and vulnerabilities of already fragile states, questions of whether or not mining is good for social and economic development grow in proportion and relevance. Africa alone hosts inordinate amounts of mineral, gold, cobalt, palladium and platinum deposits enticing foreign interests and heavy Chinese investment. Often, however, such vast resource wealth in the hands of foreign corporate entities combined with poor regulation and state corruption raises grave concerns over equitable revenue sharing, land ownership rights, and respect for fundamental human rights. The world’s rapacious appetite for natural resources, metallic, and mineral goods necessary to fuel the digital lives of western societies and quench the ever-deepening thirst of Chinese industrialists has once again turned the continent into a modern epicenter of slavery.

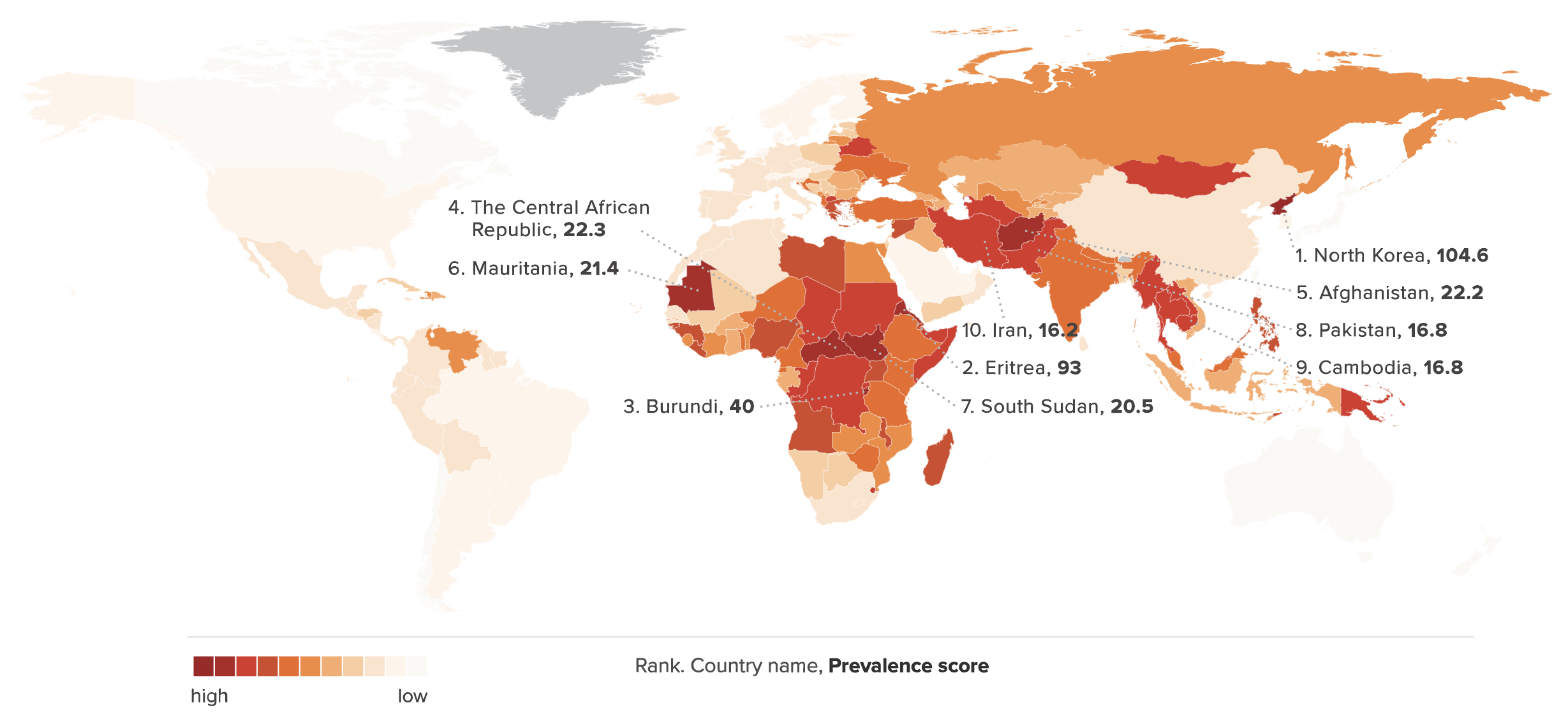

According to the 2018 Global Slavery Index, an estimated 40.3 million men, women, and children were victims of modern slavery. Women and girls made up 71 percent of victims. Modern slavery is most prevalent in Africa, where 9.2 million live in servitude, followed by Asia and the Pacific region. State-imposed forced labor and forced marriages constitute the primary culprits of enslavement, which are compounded by recurrent or protracted bouts of armed conflict, especially in fragile and grossly underdeveloped states, such as Burundi, Eritrea, or Mauritania. Slavery or enslavement is a distinct legal concept. It is defined in Article 7(2)(c) of the Rome Statute as “the exercise of any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership over a person and includes the exercise of such power in the course of trafficking in person, in particular women and children.” The 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery regards slavery as being constituted by four states of servitude, among them debt bondage, servile marriage, exploitation of children, and serfdom. Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), on the other hand, in Article 8 prohibits the use of forced or compulsory labor and provides for the opportunity to freely choose the means of one’s gainful employment. Forced labor must not entail an element of ownership to constitute slavery but many forms of slavery often involve forced labor which can take many forms, including forced labor exploitation, forced sexual exploitation, and state-imposed slavery, which persists in contravention of Article 4 of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. In Mauritania, for instance, individuals become property of their masters, who exercise total ownership over their human ‘property’ and over their descendants. It is not uncommon for slaves, which account for an estimated 155,000 of population, to be inherited by family, to be bought, sold or rented out, and be given away as gifts.

Children are especially prone to various forms of enslavement and become particularly vulnerable to conditions involving forced labor. “Worldwide, 218 million children between ages 4 and 17 are in employment. Among them 152 million are victims of child labor; almost half of them, 73 million, work in hazardous child labor.” One in four victims of modern slavery is a child.

The resurgence of widespread and pervasive forms of modern slavery on the African continent coincides with the reinvigoration of the mining industry, which in turn, benefits from an amalgamation of human vulnerabilities. Poverty and civil conflict, fragile peace, debilitated post-conflict economy, low income, poor health and education of the general population increase opportunities for debt-bondage and resource depletion through unauthorized, poorly monitored and rudimentary illicit digging. Economies of fragile or underdeveloped states remain subservient to governmental fiat whose monopoly on the means of production open prospects for graft and political corruption. Military rule and state ownership of key resource extraction industries on the continent, on the other hand, contributes to the prolongation of civil wars and rebellions, growth of the black market and rise in organized criminal activity. Resource-rich African countries like Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, to name but a few, have long suffered from the consequences of internal skirmishes, conflicts and outbursts of unstable peace, while also being home to substantial mineral, gem and diamond deposits. This paradox of plenty combined with poor growth and anemic developmental outcomes has been dubbed by scholars as the resource curse, which does not go unnoticed by enterprising Western as well as also increasingly Chinese resource extraction entities.

Africa’s wealth…

Africa “hosts 30% of the earth’s mineral reserves, including 40% of gold, 60% of cobalt, and 70% of platinum deposits, and produces about 30% of the world’s gold, 70% of the world’s platinum, 28% of the world’s palladium, and 16% of the world’s bauxite … and 595,507 kg of gold-bearing ores.” The Democratic Republic of Congo, alone, according to Forbes, is endowed with over $24 trillion worth of untapped mineral deposits, including copper, diamonds, and coltan. The promise of high earnings potential combined with an unquenchable hunger for key mineral resources by China boosts foreign direct investment on the continent, stimulating an export economy, encouraging large-scale labor migration, and feeding irregular smuggling industries. Employment of child labor in mining is not uncommon and the involvement of political classes in resource extraction profiteering – by legal and illegal means – contributes to an exacerbation of already anomalous patterns in income and wealth distribution in fragile, poverty-stricken yet resource-rich African states. Even the established agrarian economies and subsistence farming become prone to major shifts in output as mining relocates workforce, supplants food production, and contributes to noticeable market declines in the agricultural sector of the economy. Poor man’s hopes of sharing in the wealth of gem, diamond and mineral deposits become dashed by revenue capture by large multinational corporations and political and organized criminal enterprises, polluting the local environment and depleting the land, while amplifying opportunities for civil unrest.

… and its inglorious colonial past

Today, the African continent faces its own peculiar set of especially difficult problems, split between a colonial past and a Chinese-dominated future. The cycles of boom and bust in the global supply chains of valuable minerals, coal, copper, uranium, gold, gems and diamonds have played an especially prominent role in Africa’s economic (under)development. Historical exploitation of the continent’s natural resources over the years put a cumulative stress on the traditional agricultural prowess of Central and Southern African states, straining familial and tribal relations and deeply affecting the moral and social fabric of its traditional orders. “Between 1867 and 1935, more than £1,200 million of public and private capital was invested in Africa.” Infusion of capital resulted in high demand for land and labor which caused “a massive decline in rural productivity” and “destroyed the economic, social, and political structures which had held African society together.” Colonial administration of African lands attracted French, German, Belgian, British, and German interests, which invested heavily in the mining industry, “whose dominant units [were] the major international corporations, that cause[d] and reproduce[d] the continent’s underdevelopment.”

The period of decolonization brought with it the globalization of the mining industry, which introduced American and Japanese stakeholders and developed new deposits in Australia and Canada, financed by the profits from Africa. Foreign interests brought capital resources, financial finesse, and technological innovation, yet profits have been one-sided and have disproportionately accrued to Western companies and their financial sponsors – large banking institutions such as Barclays, Deutsche Bank, or First National City Bank of New York – who upon entering into agreements with African governments were guaranteed unobstructed market access and little to none opposition to their projects, while Africa descended into poverty, civil conflict, and war. Between 1868 and 1928, the South African diamond- and gold-mining industry alone generated “£340 million worth of diamonds, while the total amount of foreign capital invested in the diamond industry was probably no more than £20 million. The dividends of the diamond-producing companies, excluding the profits made by the individual diggers, exceeded £80 million.” Any foreign investments made around the African mineral resource economy were made to ensure the infrastructurally sound and reliable access and export of the mined goods. Investments in transportation links – railways and river barges – had been made to link Africa’s mineral wealth to the main trading routes that fed into the global economy; they had not been made to equip the continent with suitable standards of living and a sure path to development and independence.

The world’s ferocious demand for Africa’s resources, over decades of Western domination and exploitation, only exacerbated the continent’s underdevelopment and increased its dependence. The scramble for Africa’s wealth encompassed material and human goods leaving the continent’s men, women and children at the mercy of the supply and demand chains of the global economy. Mining in Zaire by near-monopolistic power of international capital, for example, “distorted the country’s social structure” through land expropriation leading to the pauperization of the peasantry and blocking the emergence of national bourgeoisie. The need for “cheap black labor” in Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) and the desire to stabilize the supply of labor force resulted in the colonial imposition of a land tax on the African population with an aim of preventing lucrative yields from land cultivation and forcing the local population into industrial mining. Despite Liberia’s position as “a country exceptionally well endowed with natural resources, of iron ore as well as diamonds and other minerals, with good soil, a huge potential in forestry and a booming export trade” the serious budgetary deficits which the country faced in 1968 were largely due to the generous concession agreements, relaxed government supervision of accounting and financial reports, and the inevitable “enormous outflow of resources to the mining companies.” Nearly a third of the country’s GNP of the monetary sector of the economy was consumed by the outflow of cash to foreign interests. Similarly, parasitic practices repeated many times over across the continent – from Zambian copper, South African gold, Namibian and Gabonese uranium, to Togolese phosphates – produced thriving Belgian, British, German, French, and American economies while sentencing Africa to the distressing Third World status. The seizure of land and deliberate suppression of indigenous industries and agricultural development is known to have been replicated by European colonial powers in French North Africa, Anglo-Dutch East and South Africa as well as India. As Shashi Tharoor has shown in Inglorious Empire: What the British Did in India (2017), when the East India Company was established in 1600, Britain accounted for a mere 1.8 percent of global GDP and India for the impressive 23 percent. In 1750, India and China together accounted for three-quarters of the global industrial output. However, by the time of India’s independence in 1947, after decades of systematic plunder and transformation by British imperial rule, India’s contribution to world GDP decreased to 3%, while Britain’s was three times as high, reversing the large imbalances of wealth and political leverage which have lasted well into the 21st century.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes

Today, Africa’s developmental path is heavily influenced by Chinese mining and resource extraction interests, substantial investments in agriculture, infrastructure, peacekeeping, and formal and informal security arrangements, which once again, set the continent firmly on the path of protracted material dependence. According to Brookings, between 2000 and 2017, China provided $143 billion in loans to African governments and their state-owned enterprises in the form of concession loans, credit lines, and development financing and pledged additional $60 billion at the 2018 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC).1 The Export-Import Bank of China loan guarantees involve confiscation of resource-rich lands in the event of default. The world’s second largest economy imports $100 billion worth of base metals every year and its interests in Sub-Saharan Africa’s natural wealth in cobalt, chromium, iron ore, copper, gold, manganese, among others, will undoubtedly change the social-economic trajectory of Ghana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Kenya, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zambia. Mining alone, however, implicates cognate conflicts over land ownership, human rights abuses, and environmental degradation on the continent. The impact of mining on the environment has already caused much disaffection and concern. Harmful levels of radioactivity and poor corporate social responsibility paired with inadequate state oversight and corruption of state and local elites threaten to further exaggerate Africa’s vulnerabilities and accelerate social and economic inequalities of already disempowered local populations. In exchange for African countries’ symbolic political support in global institutions and multilateral fora, China – in substantially instrumental yet strategic ways – is gobbling up Africa’s vast natural resource wealth in order to ensure its own global dominance by 2049, the centennial of China’s Communist Revolution.

The many temptations of Chinese direct foreign investment in largely acquiescent Africa are bound to overlook the substantial human cost of forced or state-sanctioned labor, which all-too-frequently assist in the states’ rapid industrialization and upward economic growth.

Despite great legal strides being made in the form of the 1926 Slavery Convention, the 1956 United Nations’ Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, Slave Trade, and Institutions and Practices Similar to Slavery, the 1976 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the 1957 Convention of the Abolition of Forced Labor, states and corporate entities are often complicit in the crime which maintains and perpetuates a system of political and economic domination and sustains structural inequalities inherent in the global economy. The illicit labor landscape is further complicated by mass population movements resulting from conflicts in North Africa and the Middle East. Vulnerable and at-risk populations turn to organized networks of smugglers and traffickers, who profit from human tragedy. Fresh supply of labor of forced and unforced nature creates opportunities for exploitation which often falls under the definitional category of ‘modern slavery’ or other forms of ‘consensual exploitation’ stemming from economic desperation offered in exchange for inhumane treatment and substandard working conditions. According to the 2005 A Global Alliance Against Forced Labour report “80 percent of forced labor is found in the private economy, mainly in the rural and informal sectors in developing countries, but also penetrating the supply chain of major companies in the developing and industrialized world alike.” Yet, the enforcement and criminalization of such practices remains elusive due in large measure to the architecture of modern demand and supply chains. Scholars even suggest that

“…the majority of victims of forced labour are not slaves of brutal war lords, dictatorial regimes or mafia-type criminal networks. They are subjected to coercion in the informal economy and in mainstream economic sectors, tied to their workplaces by subtle means of coercion and control… their exploitation is part and parcel of labour relations in certain parts of the economy.”2

Can international criminal law be an effective instrument against modern slavery?

The present-day landscape of corporate- and government- level initiatives attempting to address and redress the transnational nature of modern slavery has been gradually populated by a set of guidelines and good practices across industries and continents. Since the enactment of International Labour Organization’s 1977 Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy, the UN Global Compact, and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises – which call for elimination of forced and child labor – governments and businesses alike have been forced to reckon with human rights abuses within their supply chains. Additionally, the Athens Ethical Principles adopted by business companies in 2006 to combat human trafficking worldwide, have espoused seven main values:

“(1) Demonstrate the position of zero tolerance towards trafficking in human beings, especially women and children for sexual exploitation (Policy Setting); (2) Contribute to prevention of trafficking in human beings including awareness-raising campaigns and education (Public Awareness-Raising); (3) Develop a corporate strategy for an anti-trafficking policy which will permeate all our activities (Strategic Planning); (4) Ensure that our personnel fully comply with our anti-trafficking policy (Personnel Policy Enforcement); (5) Encourage business partners, including suppliers, to apply ethical principles against human trafficking (Supply Chain Tracing); (6) In an effort to increase enforcement it is necessary to call on governments to initiate a process of revision of laws and regulations that are directly or indirectly related to enhancing anti-trafficking policies (Government Advocacy); (7) Report and share information on best practices (Transparency).”3

The identification, prevention, and mitigation of human trafficking, forced labor, and human rights abuses propelled by sporadic intensification of stakeholder pressures and generalized public boycotts, could benefit, however, from the assistance of regulators and law enforcement entities. By criminalizing behavior of companies and governments and holding them accountable for falling short on their commitments to the minimization of opportunities for human exploitation are severely overdue steps in the corporate responsibility and state liability discourse and practice. Domestic and international legal and criminal liability might be an effective last resort in incentivizing human rights compliance in both mainstream and informal sectors of the economy and broader state development schemes. The International Criminal Court (ICC) with its comprehensive transnational legal mandate can be a powerful institutional weapon in the fight against modern forms of slavery, which can ensure a modicum of accountability and just satisfaction as it prospectively endeavors to redress the all-too-prevalent abrogation of human, civil, and political rights. Strategic litigation that draws on international criminal law – be it through the ICC or other international judicial mechanisms – can provide a requisite roadmap to future prosecution of offenses of universally objectionable nature and issue an authoritative statement on crimes shocking to the human conscience.

1 Y. Sun. 2020. “China and Africa’s debt: Yes to relief, no to blanket forgiveness” https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2020/04/20/china-and-africas-debt-yes-to-relief-no-to-blanket-forgiveness/

2 B. Andrees, “Defending Rights, Security Justice: The International Labor Organization’s Work on Forced Labor” JICJ. 343-362.

3 Business and Human Rights Resource Centre. “The Athens Ethical Principles” https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/pdf-athens-ethical-principles

About the Author

Joanna Rozpedowski

Dr. Joanna Rozpedowski is a Policy Fellow at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George

Mason University. She can be found on Twitter @JKRozpedowski.