Since the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9th, 1989, the United States held an unparalleled political, economic, and military position in the post-communist era. For nearly three decades, liberal values propped up by an unrivaled technological superiority outpaced its European allies and dwarfed the concerted efforts of Asian and Latin American developing nations. International organizations, such as NATO, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization facilitated cooperation among nations and created incentives for states to work together.[i] Consecutive international agreements, treaties, and conventions aimed to stabilize regions, resolve disputes and deep conflicts of interest, and remedy residual power imbalances which thwarted institutional cohesion and domestic prosperity. The rising tides of economic globalization promised to lift all boats.

Yet, “instead of a peaceful world order and near-universal acceptance of benevolent U.S. leadership,” as one well-regarded international scholars has indicated, “the post-Cold War world continued to operate according to the more traditional dictates of realpolitik”[ii] necessitating extensive budgetary commitments to the U.S. security and military. The increase in total global wealth failed to sufficiently proof emerging democracies against the likelihood of war and the 2001 treaty of friendship and cooperation between the United States and China came to yield contrasting dividends in 2020. The U.S.’ “constructive relationship” with China and a “special relationship” with Russia have been outpaced by Chinese appropriation and near-monopolistic power over global supply chains, aggressive Russian exercise missions in the Arctic, the Baltic, and the outer space, and further exacerbated by the pandemic-affected social, political, and economic realities on the ground.

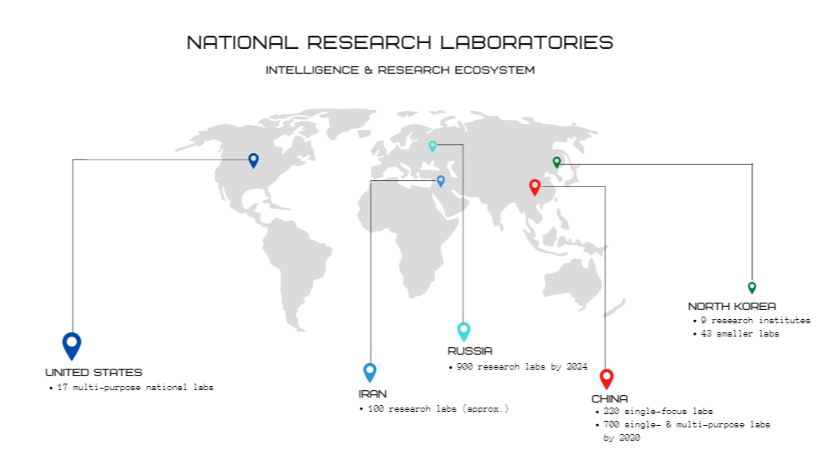

The National Defense Strategies issued in the past three years have acknowledged an “increasingly complex global security environment, characterized by overt challenges to the free and open international order.”[iii] For the authors of the NDS 2018, it has become gradually more apparent that China and Russia strive to shape a world that is consistent with their authoritarian model, while Iran and North Korea seek to guarantee regime survival and increased leverage by seeking nuclear, biological, chemical, conventional, and unconventional weapons.[iv]

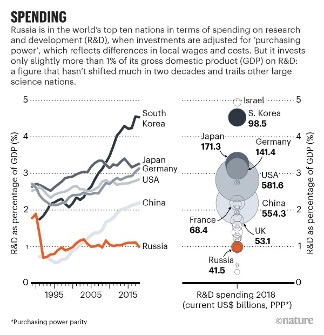

The new millennium has thus been marked by rapid technological and social change provoking geopolitical realignments, regional power struggles, and unabated military, research, and economic rivalry. The United States recognizes that international strategic competition between trade partners as well as political foes is on the rise and that it must adjust its national security and defense strategies to unilaterally meet the emerging challenges.[v]

What’s at issue

In the next great power competition, traditional forms of kinetic warfare will undoubtedly give way to simulated but not less effective non-military methods involving close collaboration between civilian and military sectors of the economy and society. These phantom warfare scenarios will likely occur in the cybersphere through unmanned agents of surveillance, manipulation of algorithmic data, and advanced use of Artificial Intelligence and drone technologies. Scientific advances will breed a new generation of sophisticated biotechnologies enabling synthetic engineering of pathogens and biological compounds which will permanently alter the national security landscape and their use for offensive and defensive purposes, will make the conduct of future conflicts a permanent feature in the military toolkit of industrialized and highly developed nations as well as developing and rising or revisionist powers seeking strategic advantage via non-traditional means.

The resulting cool war – or “an on-going conflict that involves constant offensive measures that seek to damage the economic health of a rival and the targeting of ‘cutting edge technologies’”[vi] – sets as its goal the maintenance of a stable thermal equilibrium preventing the conflict from turning hot or resulting in full kinetic or nuclear engagement.

Non-kinetic violence unleashed to maximize political and economic goals will be accompanied by a considerable diffusion of power across networks of state and non-state actors capable of inflicting damage to vital state interests without the possibility of being traced, actively monitored, or prevented by current legal and extra-legal systems in place. Future theaters or war will undoubtedly blur conventional lines of distinction drawn in international law between civilians and combatants, international and non-international conflicts as well as challenge states’ responses to asymmetric warfare and the degree of proportionality required to effectively repel unconventional attacks on state-owned infrastructure and resources.

The post-9/11 intelligence threat assessments focused heavily on biological weapons in the hands of terrorist groups. Substances such as anthrax, smallpox, and other conventional biological agents comprised a list of the most likely culprits instigating terror on a global scale. As late as 2017, Homeland Security cited concerns with threats of bioterrorism which included high-profile disease outbreaks, such as Ebola and viruses like dengue, chikungunya, and Zika.[vii] Highly virulent compounds and substances resulting from marked improvements in nanotechnologies and bio-engineering can also constitute a novel form of asymmetrical “hybrid” conflict defined by the NATO 2014 Wales Summit Declaration as a specific set of challenges and threats (including cyber and terrorism) “where a wide range of overt and covert military, paramilitary, and civilian measures are employed in a highly integrated design.”[viii]

There is a reason, therefore, to assume that bio- incidents will, in the future as much as they had in their disreputable past, become once again more fully integrated into the “hybrid” warfare design and constitute, along with cyber and terrorism, a (re)emerging threat paradigm in the new state-power competition.

The White House’s 2018 Biodefense Strategy in alignment with the 2018 National Defense Strategy identifies biological threats – whether naturally, occurring, accidental, or deliberate in origin – as among the most serious challenges facing the United States and the international community.[ix] The document puts significant emphasis on enhancing the national bio-defense enterprise to protect the United States and its partners abroad from biological incidents. It sets out five goals and objectives for ameliorating the risks stemming from the evolving biological risk landscape. They are: (i) Enabling risk awareness to inform decision-making across the bio-defense enterprise; (ii) Ensuring bio-defense capabilities to prevent bio-incidents; (iii) Ensuring bio-defense enterprise preparedness to reduce the impacts of bio-incidents; (iv) Rapidly responding to limit the impacts of bio-incidents; (v) Facilitating recovery to restore the community, the economy, and the environment after a bio-incident.

The United States Government Accountability Office’s “National Biodefense Strategy” report underscored, however, several lapses in the 2018 Biodefense Strategy Report, such as lack of “clearly documented methods, guidance, processes, and roles and responsibilities for enterprise-wide decision-making”[x] complicating coordination of response mechanisms to bio-incidents thus putting the initiative in danger of failing to meet its long-term bio-defense objectives.

In recognition of the changing threat environment, the Trump Administration’s 2021 budget priority requests call for $740.5 billion for national security, $705.4 billion of which will be dedicated to the Department of Defense’s investment priorities, which include building a more lethal, agile, and innovative joint force.[xi]

An overview of funds allocation demonstrates an emphasis on traditional tools and methods of warfare, such as nuclear modernization ($28.9 billion), missile defeat and defense ($20.3 billion); munitions ($21.3 billion) as well as newer frontiers of potential conflict, including cyberspace ($9.8 billion) and the space domain ($18.0 billion). The proposed budget also anticipates expenditures in bio-research but does not explicitly support or articulate specific bio-weapons defense research and development objectives. Its investments in bio-technologies focus on (1) “$1.3 billion for the Agricultural Research Service, which conducts in-house basic and applied research, develop vaccines, and provide enhanced diagnostic capabilities to protect against emerging foreign animal and zoonotic diseases that threaten the Nation’s food supply, agricultural economy, and public health.”[xii] (2) “$14 billion investment in DOD science and technology programs that support key investments in industries of the future, such as artificial intelligence, quantum information science, and biotechnology.” (3) “HHS bio-defense and emergency preparedness procurement through the BioShield program and the Strategic National Stockpile, and includes $175 million to support Centers for Disease Control’s global health security activities, an increase of $50 million compared to the 2020 enacted level.”[xiii]

The United States continues to invest heavily in medical intelligence under the auspices of the Department of Defense to monitor the research terrain in order to identify the known knowns and known unknowns.

Bio-events: Who’s in Charge?

The Departments of Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Agriculture have been tasked with bio-surveillance responsibilities, which include developing personnel, training, equipment, and systems to support a national bio-surveillance capability.[xiv] As of May 2020, Homeland Security has been working on future-oriented enhancements comprising of:

- The Enhanced Passive Surveillance program geared toward delivering a “surveillance system for identifying endemic, transboundary and emerging disease outbreaks in livestock…and identify trigger points to alert officials for action.”

- The BioThreat Awareness APEX program will “develop affordable, effective and rapid detection systems and architectures to provide advance warning of a biological attack at indoor, outdoor and national security events.”

- The Bio-surveillance Information and Knowledge Integration Program seeks to develop a Community of Practice (COP) Platform prototype that integrates multiple data streams to support decision making during a biological event as well as inform training tools for state responders.”[xv]

The programs here enumerated aim to complement the existing systems in place, including the BioWatch program managed by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Health Affairs monitoring aerosol releases of select biological agents, natural and man-made as well as the Department of Defense’s Airbase/Port Detector System or Portal Shield System designed to provide early warning of biological threats to high-value assets, such as air bases and port facilities.[xvi]

The 2010 Report to Congress issued by the US Government Accountability Office claims, however, that “there is neither a comprehensive national strategy nor a focal point with the authority and resources to guide the effort to develop a national bio-surveillance capability” and that “efforts to develop a bio-surveillance system could benefit from a focal point that provides leadership for the interagency community.”[xvii]

From bio-surveillance to bio-security

The bio-engineering and disease outbreak threat environment has called for streamlining of knowledge and intelligence sharing to detect and effectively respond to bio-hazards. In the United States, bio-surveillance defined as “the process of gathering, integrating, interpreting, and communicating essential information related to all hazards, threats, or disease activity affecting human, animal, or plant health to achieve early detection and warning, [which] contribute to overall situational awareness of the health aspects of an incident, and to enable better decision-making at all levels”[xviii] is regulated by three legislative measures – The Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 (IRCA), the FDA Food and Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), and the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Reauthorization Act of 2013 (PAHPRA).[xix] At the national level, the bio-surveillance regime functions include: (i) gathering, integrating, analyzing, interpreting, and disseminating data utilizing a coordinated governance structure; (ii) monitor incidents, threats, or activities in the human, animal, and plant environment; and (iii) enable early detection of threats and mounting an integrated response.[xx] Globally, International Health Regulations aim to promote national-level surveillance, detection, dissemination of incident-related information to World Health Organization members, ensure verification, and put in place response protocols.[xxi]

Global outlook

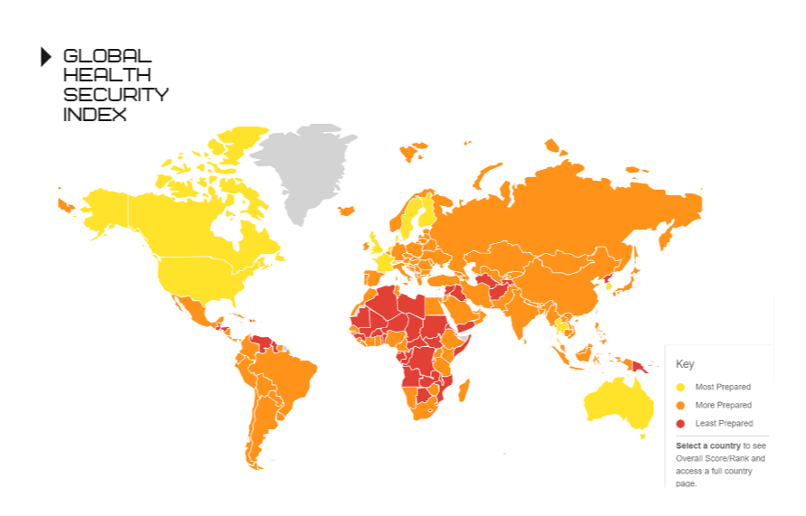

Global Health Security Index prepared by Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in collaboration with NTI found that the international preparedness for epidemics and pandemics of natural or synthetic occurrence remains very weak with an average overall GHS Index score of 40.2 out of a possible 100.[xxii] High-income countries demonstrate greater preparedness and score higher on disease prevention, bio-safety, and bio-security measures. While public health and economic resilience as well as political and security risks challenge developing nations and regions.

The art of the possible

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2018 Bio-defense in the Age of Synthetic Biology Report enumerates ways in which synthetically engineered pathogens can alter the national security landscape. Advances in genetics, may “soon make possible the development of ethnic bio-weapons that target specific ethnic or racial groups based upon genetic markers.”[xxiii] Targeted bio-weapons systems might favor ethnically heterogeneous nations i.e. the USA over homogeneous ones such as China or Russia.[xxiv]

Concerns over the speed of scientific advances and acceleration in the ability to create or modify biological organisms is an area of significant interest to the defense community. A new generation of bio-weapons can target specific animals or plants, crippling agricultural output, sabotaging supply chains, and threatening the stability of political systems and continuity of economic activities. Herbicidal warfare intended to destroy crops and defoliate vegetation has already been used in the 1960s and ’70s Sino- Soviet and Vietnam counterinsurgency operations and the United States sabotaged Soviet agricultural output with chemical and entomological capabilities during the Cold War.

The 1976 Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques, while a legal deterrent meant to bring about general and complete disarmament and thus “saving mankind from the danger of using new means of warfare”,[xxv] does not thwart scientific research, testing, development, and use of tactical herbicides for peaceful purposes.

Meanwhile, biotechnological innovations offer new and improved capabilities. Experts see the emerging field of synthetic biology as a highly malleable science enabling (i) modifications to the human immune system; (ii) modifications to the human genome; (iii) re-creating known pathogenic viruses; (iv) making existing bacteria more dangerous; and (v) creating new pathogens.[xxvi] Each of these comes with its own set of expertise requirements, levels of usability as a bio-weapon, and a specific set of risks outlined in the enclosed graphic.

While advances in synthetic biology promise to account for a wide range of biological anomalies by providing revolutionary diagnostic and therapeutic tools, they can also increase the power of malicious actors intent on creating tailor-made harmful biological agents and expand what is possible in the creation cycle of new bio-weapons.

Bio-events: Legality and liability

The Hague Declaration of 1899 lays down principles preventing the use of certain methods of combat that are outside of the scope of civilized warfare and reiterated in the 1925 Geneva Protocol. Chief among them was the prohibition on the use and dispersal of asphyxiating, poisonous or deleterious gases, and bacteriological methods of warfare. Following World War I, the international community further banned the use of chemical and biological weapons, and the 1972 Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) and the 1993 Chemical Weapons Conventions further prohibited the development, production, stockpiling, and transfer of these weapons and the use of biological agents in armed conflict constitutes a war crime under the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.[xxvii]

The BTWC does not explicitly prohibit the “use” of biological weapons, however, the Final Declaration of the 1996 Treaty Review Conference reaffirmed that under Article I of the BTWC, any alleged “use” is tantamount to a violation of the Convention.[xxviii]

The UN Security Council Resolution 1540 calls upon countries to establish and enforce laws prohibiting and preventing the acquisition and transfer of biological weapon-related materials and equipment. There are, however, limited formal verification mechanisms and biological and chemical weapons still pose a significant threat to national security as do synthetically manufactured compounds resulting from scientific and bio-engineering advancement and innovation.[xxix]

Remedies

Short of risky and questionable military intervention, states adversely affected by a bio- event can seek remedies in international fora. Legal mechanisms in existence permit state parties to international treaties, agreements, and conventions to utilize pathways created by international arbitration mechanisms to seek reparations for breaches of international law.

Thus, state parties injured by “wrongful acts” of a state can rely upon the remedial mechanisms contained in the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR). Parties seeking a remedy can take advantage of Article 56 of IHR (2005) setting out procedures for the settlement of disputes through negotiation, mediation, or conciliation. And in the instance of deep conflicts, refer the case to the World Health Organization’s Director-General.

Second, the International Court of Justice and Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague can offer venues for settling legal disputes to all members of the United Nations who accept the court’s jurisdiction. Litigation between state parties can proceed based on relevant treaties.

Third, the World Trade Organization’s dispute resolution mechanism can be mobilized to settle trade-related disputes but also, based on the previous precedent, establish grounds for holding state parties accountable for deviations from the WTO obligations.

Fourth, bilateral Investment Treaties provide mechanisms for settlement and dispute resolution of inter-state nature between parties to the agreement.

Lastly, legal remedies at the domestic level are limited by the principle of sovereign immunity, “however, cases implicating individuals, corporations, and state parties that caused widespread injuries and damages” can be pursued, with varying degrees of success, in U.S. Federal Courts.[xxx]

In the above mentioned, questions of jurisdiction, admissibility of claims, and sovereign immunity will condition the legal prospects and factual merits of the case. Response to state crimes is governed by four principal punishment mechanisms: (1) retribution; (2) deterrence; (3) rehabilitation; and (4) incapacitation.[xxxi] Their selective implementation seeks to achieve a modicum of restorative justice. Practical tools available to state parties pursuing remedies for damaging bio-events, short of military action, can include visa and financial sanctions and imposition of detrimental export-import tariffs.

The path forward

To mitigate the risks issuing from a rapid pace of technological and biotechnological progress, the international community must invest in the promotion and enforcement of norms of responsible conduct and strengthening the public health infrastructure to detect and effectively respond to disease outbreaks of natural and synthetic nature.[xxxii]

Because it is often difficult to distinguish between legitimate research laboratories of national, private/commercial, or academic character and non-legitimate ones, dual-use research is going to remain a compounding challenge. With growing knowledge of the human genome and the human immune system, the risk of synthetic manipulations to modulate human physiognomy increases proportionally as do varying ways of arming pathogens, biochemicals, and toxins to usher in the age of geopolitical realignment.

In sum, the latest advances in genetics and bio-engineering as well as growing ambitions of revisionist states — including China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia — require that a new conceptual and real frontier of great and emerging power competition in the area of biological warfare commands renewed attention. While advances in synthetic biology promise to account for a wide range of biological anomalies by providing revolutionary diagnostic and therapeutic tools, they can also increase the power of malicious actors intent on creating tailor-made harmful biological agents. Synthetically engineered pathogens can significantly alter the national security landscape.

The digitalization of life sciences and the rise of accessible gene-editing tools introduce vulnerabilities that should be of concern to policy-makers and the national bio-security community. Global Health Security Index prepared by Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security found that the international preparedness for epidemics and pandemics of natural or synthetic occurrence remains very weak. The weaponization of viruses and bio-engineered genetic mutation of existing diseases and pathogens to inflict maximum harm will be a preferred weapon of choice for revisionist powers seeking to destabilize democratic regimes, topple governments, cripple supply chains, and shock economic cycles. Strengthening international investigatory and legal mechanisms to hold perpetrators of first-use of biological weapons criminally and financially liable for the harms inflicted and damages done should therefore be a top priority for the international community and its global increasingly wavering governance institutions.

Selected Bibliography

Huff, A.G. et al., “Biosurveillance: a systematic review of global infectious disease surveillance systems from 1900 to 2016”, Revue Scientifique et Technique, 36(2).

International Committee of the Red Cross. 2013. “Chemical and Biological Weapons” https://www.icrc.org/en/document/chemical-biological-weapons

National Academy of Sciences. 2018. “Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology”. https://www.nap.edu/read/24890/chapter/1.

Rothkopf, David, “The Cool War”, Foreign Policy, 2013. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/02/20/the- cool-war/

United States Government Accountability Office. 2020. National Biodefense Strategy – Report to Congress. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/704698.pdf.

Walt, Stephen M. The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy, (New York: Ferrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018).

References

[i] Stephen M. Walt, The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy, (New York: Ferrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018). p. 71.

[ii] Stephen M. Walt, The Hell of Good Intentions: America’s Foreign Policy Elite and the Decline of U.S. Primacy, (New York: Ferrar, Straus & Giroux, 2018). p. 74.

[iii] United States Department of Defense. 2018. National Defense Strategy: Summary. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf p. 2.

[iv] United States Department of Defense. 2018. National Defense Strategy: Summary. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf p. 2.

[v] Anthony Cordesman, “China’s New 2019 Defense White Paper” Center for Strategic and International Studies, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-new-2019-defense-white-paper

[vi] David Rothkopf, “The Cool War”, Foreign Policy, 2013. https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/02/20/the-cool-war/

[vii] United States Government Accountability Office, “National Biodefense Strategy – Report to Congress”, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/704698.pdf. p. 50.

[viii] Antonio Missiroli, “From Hybrid Warfare to ‘Cybrid’ Campaigns. The New Normal?” CSS ETH Zurich, 2019. https://css.ethz.ch/en/services/digital-library/articles/article.html/a59d89dd-1179-453b-ab02-ade9097cf646

[ix] U.S. Homeland Security. 2018. The National Biodefense Strategy. https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=815921. p. i. [10] United States Government Accountability Office, “National Biodefense Strategy – Report to Congress”, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/704698.pdf. p. 1.

[x] United States Government Accountability Office, “National Biodefense Strategy – Report to Congress”, 2020. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/704698.pdf. p. 1.

[xi] DOD Releases Fiscal Year 2021 Budget Proposal https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2079489/dod-releases-fiscal-year-2021-budget-proposal/

[xii] Office of Management and Budget, “Budget of the United States Government” Fiscal Year 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/budget_fy21.pdf

[xiii] Office of Management and Budget, “Budget of the United States Government” Fiscal Year 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/budget_fy21.pdf

[xiv] United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees, “BIOSURVEILLANCE: Efforts to Develop a National Biosurveillance Capability Need a National Strategy and a Designated Leader”, 2010, https://www.gao.gov/assets/310/306362.pdf

[xv] U.S. Homeland Security, “CBD Focus Areas – Biosurveillance”, 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/biosurveillance

[xvi] United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees, “BIOSURVEILLANCE: Efforts to Develop a National Biosurveillance Capability Need a National Strategy and a Designated Leader”, 2010, https://www.gao.gov/assets/310/306362.pdf, p. 69.

[xvii] United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees, “BIOSURVEILLANCE: Efforts to Develop a National Biosurveillance Capability Need a National Strategy and a Designated Leader”, 2010, https://www.gao.gov/assets/310/306362.pdf, preface.

[xviii] A.G. Huff et al., “Biosurveillance: a systematic review of global infectious disease surveillance systems from 1900 to 2016”, Revue Scientifique et Technique, 36(2), p. 513.

[xix] Amanda J. Kim and Sangwoo Tak, “Implementation System of a Biosurveillance System in the Republic of Korea and its Legal Ramifications”, Health Security Vol 17 (6). p. 463.

[xx] Amanda J. Kim and Sangwoo Tak, “Implementation System of a Biosurveillance System in the Republic of Korea and its Legal Ramifications”, Health Security Vol 17 (6). p. 463.

[xxi] Amanda J. Kim and Sangwoo Tak, “Implementation System of a Biosurveillance System in the Republic of Korea and its Legal Ramifications”, Health Security Vol 17 (6). p. 464.

[xxii] Johns Hopkins University. 2019.Global Health Security Index https://www.ghsindex.org/

[xxiii] J.M. Appel, “Is all fair in biological warfare? The controversy over genetically engineered biological weapons,” Global Medical Ethics (2009: 35), p. 429.

[xxiv] J.M. Appel, “Is all fair in biological warfare? The controversy over genetically engineered biological weapons,” Global Medical Ethics (2009: 35), p. 430.

[xxv] Adam Roberts and Richard Guelff. 2010. Documents on the Laws of War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 155.

[xxvi] National Academy of Sciences. 2018. “Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology”, https://www.nap.edu/read/24890/chapter/1. p. 117.

[xxvii] International Committee of the Red Cross. 2013. “Chemical and Biological Weapons” https://www.icrc.org/en/document/chemical-biological-weapons

[xxviii] NTI, “The Biological Weapons Convention” , 2003, https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/biological-weapons-convention/

[xxix] Office of Disarmament Affairs, “UN Security Council Resolution 1540”, https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/sc1540/

[xxx] Matthew Henderson et al. “Corona-virus Compensationn? Assessing China’s Potential Culpability and Avenues of Legal Response”, (April, 2020), https://henryjacksonsociety.org/wp- content/uploads/2020/04/Coronavirus-Compensation.pdf

[xxxi] Jennifer Marson, “The History of Punishment: What Works for State Crime?”, The Hilltop Review , (Spring 2015: 2:7).

[xxxii] National Academy of Sciences. 2018. “Biodefense in the Age of Synthetic Biology”. https://www.nap.edu/read/24890/chapter/1. p 13.

About the Author

Joanna Rozpedowski

Dr. Joanna Rozpedowski is a Policy Fellow at the Schar School of Policy and Government at George

Mason University. She can be found on Twitter @JKRozpedowski.