In the wake of the AUKUS agreement, EU member states must come to terms with the loss of primacy and the shift of the U.S.’s geostrategic center of gravity to the East to counter Chinese expansionism. The old Eurocentric western security architecture is essentially in shambles, hindering NATO’s integrity as well. The emerging “Quad” alliance between the U.S., U.K., Australia, India, and Japan diminishes NATO’s importance in the Indo-Pacific. The French and other traditional allies and partners—members of EU and NATO—collectively appeared more enraged than China, highlighting the clumsy formation of AUKUS that was accelerated by the Afghanistan withdrawal debacle. AUKUS marks a turning point in global geopolitics that will have a domino effect on several parts of the world—one being the Eastern Mediterranean.

After the diplomatic blow of AUKUS and Angela Merkel’s retirement from frontline politics, France’s first reaction was to strengthen its ties with Greece and increase its presence in the Eastern Mediterranean by signing a rearmament deal that modernizes the Hellenic Navy and commits to an important Defense Assistance Agreement. The latter includes a clause of mutual defense assistance—similar to the mutual defense clause (Article 42.7 TEU) of the Treaty of the European Union—in case one of the two states is attacked on its territory.

Analysts note a relation between AUKUS and U.S. support for France to pursue a more proactive role in the Eastern Mediterranean through the game-changing Franco-Greek deal that bolsters the Greek armed forces with three Belharra frigates (+1 option). Athens previously ordered 18 Rafale fighter jets and has plans to acquire six more in the future.

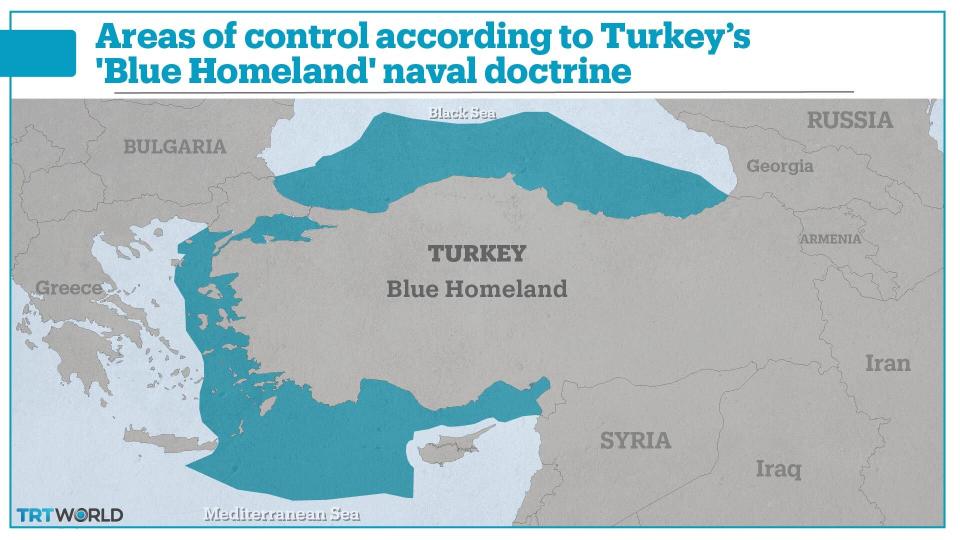

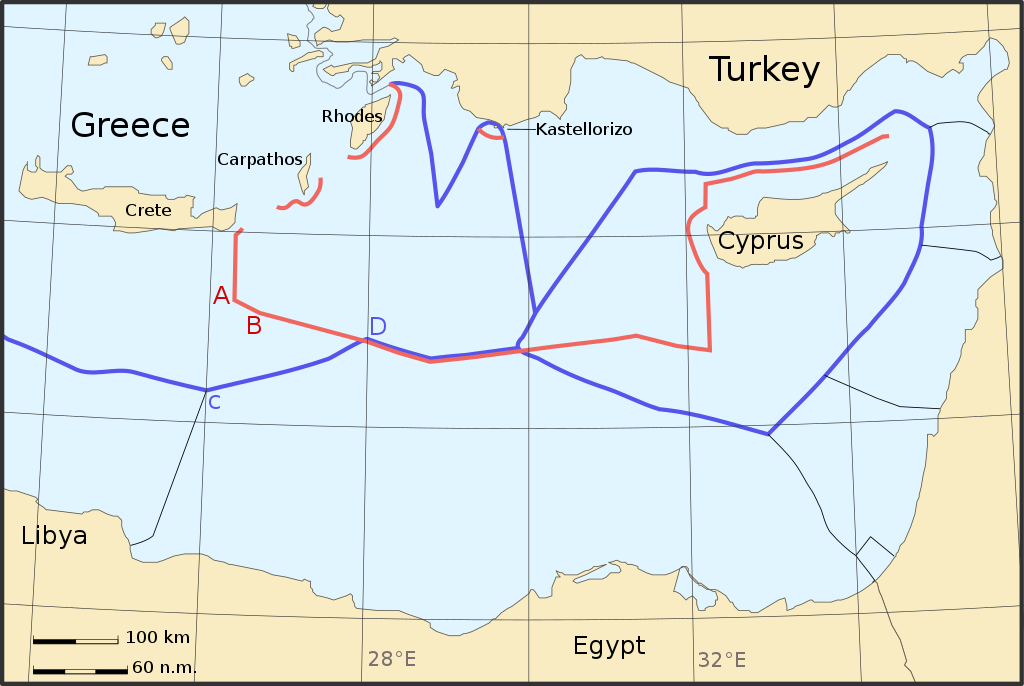

France already showed its intention to support Greece against Turkey during a prolonged 82-day crisis that brought Greece and Turkey (two historic rivals and NATO members) to the brink of conflict. Back in 2020, the Turks deployed their seismic research vessel Oruç Reis accompanied by a flotilla of warships to conduct surveys on the Greek continental shelf (as described in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – UNCLOS III) that Turkey claims with the unsubstantiated Mavi Vatan (Blue Homeland) naval doctrine. The Mavi Vatan opposes UNCLOS III provisions and is based on the arbitrary assumption that all islands are deprived of the right to exert jurisdiction on the continental shelf. However, the Law of the Sea is binding on all states to the extent that it represents customary international law, and although Turkey is not a signatory to it, it has to comply with it.

French President Emmanuel Macron openly criticizing Turkey’s activity on the Greek and Cypriot continental shelf/exclusive economic zone (EEZ) said, “I don’t consider that in recent years Turkey’s strategy is the strategy of a NATO ally… when you have a country which attacks the exclusive economic zones or the sovereignty of two members of the European Union.” In contrast, on another occasion, he clarified that “France has been very clear. When there were unilateral acts in the eastern Mediterranean, we condemned them with words, and we acted by sending frigates.” After signing the Franco-Greek deal in Élysée Palace, he also noted that “it will help protect the sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity of both states.”

France’s intervention came as no surprise since it has competing interests with Turkey over Syria, Lebanon, and Africa. As Professor of Geopolitics Kostas Grivas explained, France has a large presence and significant geopolitical interests in Africa. Its strategic depth is in Africa, incorporating more than the Francophone states.

The Mediterranean is bridging France with the African continent; thus is imperative to maintain control of it, especially after the recently discovered energy resources attracting a great deal of interest. This brings France closer to Greece, and the Republic of Cyprus in a containment effort against Turkey’s expansionism left unanswered by the EU’s inability to guard its outermost borders.

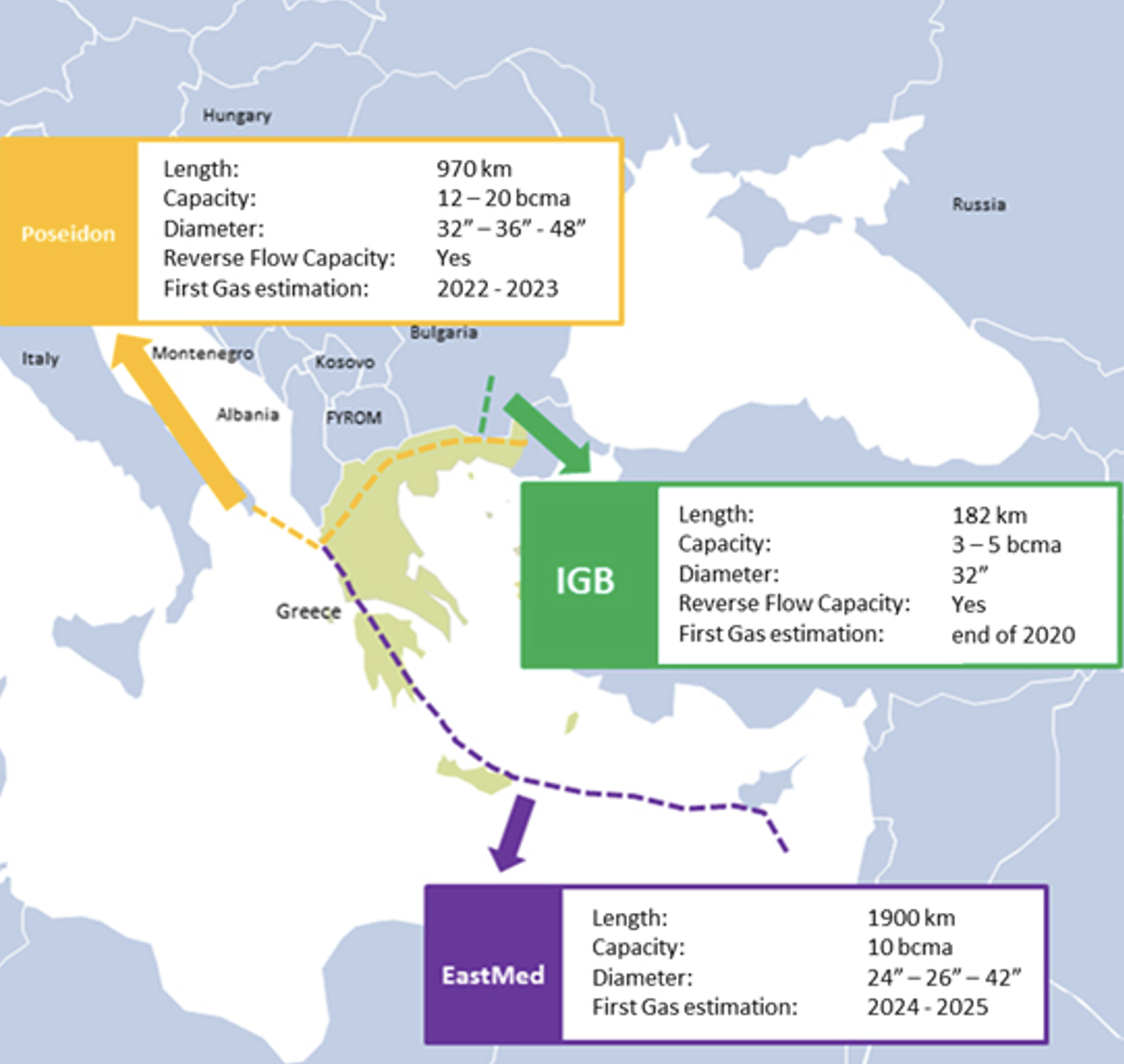

The Turks, as expected, expressed their frustration with the newly formed Franco-Greek strategic alliance by putting pressure on Greece and the Republic of Cyprus. Turkish frigates obstructed the Maltese-flagged research vessel Nautical Geo hired to conduct research related to the EastMed gas pipeline. The ship attempted to work on the Greek continental shelf and Exclusive Economic Zone (delimitated with Egypt) and Cypriot EEZ (delimitated with Egypt). Turkey, however, is claiming the same continental self with the Mavi Vatan doctrine.

With an increased military presence, the Turks aimed and succeeded in forcing the Americans on yet another equidistance statement. A State Department spokesman said the U.S. “encourages all states to resolve maritime delimitation issues through peaceful dialogue and in accordance with international law,” an announcement that overlooks the fact that the Turkish frigate obstructed Nautical Geo’s work on Greek and Cypriot delineated EEZs.

Ankara fueled tensions to test the Franco-Greek alliance’s credibility and the commitment of the states involved in EastMed. In an older statement, the Turkish Ambassador to Athens Burak Özügergin said that “the cause of our troubles [between Greece and Turkey] is Cyprus and the trilateral agreement [Greece-Republic of Cyprus-Israel] on EastMed.” On the other hand, the Israeli Ambassador to Athens, Yossi Amrani, made an ambiguous statement about the pipeline clarifying that “if we do not do it now, it will not be realistic later.”

The Americans also expressed skepticism over the feasibility and construction costs of the pipeline. “We basically support the concept of a pipeline – it’s very appealing. The question is whether it is economically viable,” an American official stated. “If the pipeline makes the gas too expensive on the European market right now, obviously that should be considered,” he added. These reservations fell into silence after Israeli interventions.

The EastMed pipeline has always faced issues with the gas deposits needed to support it. The Israeli-Egyptian agreement on the construction of a subsea gas pipeline from the Israeli Leviathan gas field (initially intended to be supplied through EastMed) to liquefaction facilities in Egypt and similar plans to transfer sizable quantities of gas from Aphrodite Cypriot gas field (also designed to be supplied through EastMed) to Egypt, raise further doubts on the project.

Dr. Charles Ellinas, a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center, counters that “due to limited amount of gas at Leviathan, it is not feasible for other pipelines from Israel to Egypt to coexist with EastMed.”

Regardless of the potential shortcomings of EastMed, it yields a unique opportunity to assess the new Franco-Greek alliance. Utilizing the proposed pipeline may prove a valuable tool to contain the Mavi Vatan revisionist doctrine. Whether EastMed is techno-economically doable or not is irrespective of the need to defend it on site. This relates to Greece’s right to unilaterally extend its territorial waters from 6 to 12Nm (in compliance with UNCLOS III provisions) as well as exercising its sovereignty rights and jurisdiction over the continental shelf/EEZ that Turkey provocatively challenges.

From France’s point of view, defending Greece’s rights (interrelated with those of the Republic of Cyprus) deriving from the Law of the Sea serves its long-term geostrategic goal for Mediterranean naval supremacy and control.

Joint Franco-Greek action to defend EastMed’s ongoing works would voice a clear message to Turkey. On the contrary, leaving the Turkish offensive obstruction of Nautical Geo unanswered would diminish the Franco-Greek pact credibility forged in common rivalry with Turkey. Moreover, the new strategic deal can act as a pretext to adopt a much-needed confrontational approach against Turkish revisionism and neo-imperial tendencies that are known to consider strong measures rather than soft diplomatic strategies.

In any case, the security situation in the region is rapidly deteriorating. Ömer Çelik (spokesperson of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s AK Party) stated on October 5, 2021, that the Mavi Vatan doctrine is Turkey’s “red line.” Days later, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu picked up the glove on the Franco-Greek alliance and increased the heat on Mediterranean waters announcing that Ankara could declare Turkey’s EEZ. How will the Greeks and French react to Turkish efforts to undermine the newly formed alliance?

About the Author

Konstantinos Apostolou-Katsaros

Konstantinos Apostolou-Katsaros is a consultant and analyst specializing in foreign affairs and Greco-Turkish relations. He holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. from the School of Environment and Technology of Brighton University (UK) where he worked as a Lecturer and Research Associate.