The sea-launched cruise missile–nuclear (SLCM-N) is a planned nuclear-armed cruise missile that is intended for deployment on US Navy submarines, potentially Virginia-class attack submarines, by 2034. Under Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) Pillar I, Australia aims to acquire three to five Virginia-class submarines from the United States by 2032. However, the US Congress must approve the sale to Australia under the AUKUS agreement. The president must certify, 270 days before the first transfer, that the sale will not degrade American undersea capabilities.

While certification is contingent on the US Navy’s ability to maintain its own submarine production rate, which is struggling to meet the planned two Virginia-class submarines per year, Australia would benefit greatly from their acquisition. Overall, it is worth noting that AUKUS Pillar I and Pillar II are likely to significantly enhance US undersea capabilities in the long term. Pillar I includes the rotational presence of one UK Astute-class submarine and up to four US Virginia-class submarines at HMAS Stirling, Western Australia, from 2027. HMAS Stirling provides the United States with greater access for the forward presence of nuclear-powered submarines in the Indo-Pacific.

Indo-Pacific access is further expanded via the new submarine base that is planned for the east coast of Australia by 2043. The authorized consolidated Commonwealth-owned Defence Precinct at Western Australia’s Henderson shipyard will provide contingency-docking and depot-level maintenance for AUKUS submarines by 2033, potentially alleviating some of the burden on US-based maintenance facilities. Pillar II will provide the advanced technology necessary to enhance US, UK, and Australian undersea capabilities, particularly for longer term advantages in mobility, survivability, lethality, and sustainability of allied forces.

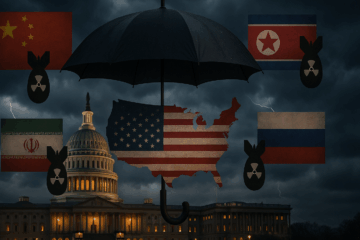

Conversely, the SLCM-N is likely a significant factor in retaining American undersea capabilities. The SLCM-N will provide the US with flexible deterrence options in austere Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres, particularly as the US needs to provide extended nuclear deterrence to 32 NATO allies plus Australia, Japan, and South Korea. There are three options to consider when attempting to deter China, North Korea, and Russia.

First, the United States can provide Australia three to five conventionally armed Virginia-class submarines. This option is likely to significantly degrade American undersea capabilities through a lack of flexible response options for strategic deterrence and extended nuclear deterrence. Plus, Australia will need to manage three classes of submarines: the Collins-class, the AUKUS-class, and the SSN-AUKUS under this option.

Second, Australia can field a dual-capable submarines (DCS) mission for Australian Virginia-class submarines. This option requires the establishment of a nuclear planning group (NPG) to plan for a DCS mission for Australian Virginia-class submarines. These submarines would be capable of carrying the SLCM-N. This nuclear-armed option is unlikely to degrade US undersea capabilities, as Australia could support some US missions in the Indo-Pacific and provide flexible deterrence options. Australia will still need to manage three submarine classes under this option.

Third, the United States does not sell Virginia-class submarines to Australia, but instead bases submarines armed with SLCM-N in Australia, either on a permanent or rotational basis. This option does not degrade US undersea capabilities. However, under this option Australia should negotiate for extended nuclear deterrence guarantees. This option is not the end of AUKUS, but Australia will need to build sovereign SSN-AUKUS submarines to fill the gap left by Australia’s aging Collins-class submarines when they are retired.

Policymakers should not be afraid to consider a flexible nuclear-armed option in light of recent and historic Russian and Chinese rhetoric on AUKUS, especially when this rhetoric concerns “non-nuclear long-range precision strike capability.” Having a nuclear-armed option would provide enough flexibility to backstop and limit conventional war.

On April 18, 2025, Russia’s envoy to Indonesia, Sergei Tolchenov, defended military ties with Jakarta and did not deny claims that Russia seeks to station long-range military aircraft at the Manuhua Air Force Base at Biak Numfor, about 1400 kilometers north of Darwin, Australia. Russia asserted that AUKUS is more of a threat to the Asia-Pacific than Russian ties with Indonesia, which are “not aimed against any third countries and poses no threat to security in the Asia-Pacific region.” Tolchenov added that challenges to regional stability

are more likely to arise from the rotational deployment of large military contingents from extra-regional states on Australian territory, including the provision of airfields for the landing of strategic bombers and port infrastructure for visits by nuclear-powered submarines. Particularly alarming are the currently discussed plans to deploy the US intermediate-range missiles in Australia, which would put ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] countries, including Indonesia, within its range, as well as the acquisition by the Royal Australian Navy of nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS trilateral partnership.

These comments are consistent with Putin’s rhetoric against the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

This is not the first time Russia and China accused the US, UK, and Australia of risking an intensified arms race and military confrontation in the Indo-Pacific. A report by the China Arms Control and Disarmament Association, China Nuclear Strategic Planning Research Institute, and the Russian Energy and Security Research Centre stated, “non-nuclear long-range precision strike capability, being provided to Australia, will affect nuclear deterrence and strategic stability.” The report goes on to say that “[w]hile current non-nuclear strategic weapons cannot carry out all the missions assigned to nuclear weapons those still can produce strategic effects.” The report further criticizes AUKUS’ nuclear submarine cooperation, which the report suggests will trigger a regional submarine arms race.

Chinese and Russian threats should not limit or contain AUKUS to non-nuclear options. This is particularly true when the US has historically provided non-nuclear long-range precision-strike capability. In the past this included the F-111 Aardvark, F/A-18F Super Hornet, E/A-18G Growler, and F-35A Lightning II.

Under the UN Charter, members have “the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence if an armed attack occurs.” Hence, Australia and its allies should stand by the expression, si vis pacem, para bellum. Australia and its AUKUS allies should not back down from non-nuclear long-range precision strike capability or nuclear-armed deterrence options that provide more flexible responses.

Although, the sale of Virginia-class submarines to Australia under the AUKUS agreement may be contingent on the US Navy’s ability to maintain its submarine production rate. It is worth noting that American undersea capabilities, particularly in the long term, may be greatly enhanced through other means under AUKUS Pillar I and Pillar II.

In the new era of nuclear disorder, the key to maintaining American undersea capabilities will likely be the SLCM-N deployed on Virginia-class attack submarines. The SLCM-N will provide AUKUS flexible deterrence options and limit risk of conflict in austere Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theatres.

Natalie A. Treloar is a Senior Analyst at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies. She is the Australian Company Director of Alpha–India Consultancy. Natalie formerly contracted to the Australian Department of Defence. Views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, policies, or positions of any organization, employer, or affiliated group.

Date for the East Coast SSN Base Ref. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/australia-submarine-capabilities/#:~:text=The%20Department%20of%20Defence%20plans,attack%20submarine%20capabilities%20(SSNs).

I am all for the nuclear armed B-21 bombers, but you aren’t likely to get them before 2034 either. Also, as Dr Christine Leah and I point out in our previous article, we have illuminated the benefits of a limited nuclear option hidden beneath the sea rather than delivered by air.

Ideally, Australia will need a modern nuclear triad (including ICBMs) in the long term to face Chinese and Russian nuclear threats.

It also depends on what missions we want our submarines to do. Are they just going to hunt down and kill other submarines, deliver a limited nuclear option? While the Los Angeles-class focuses on open-ocean anti-submarine warfare and land-based missile strikes, the Virginia-class is designed for a broader range of missions, including littoral operations and special operations support.

Last time that I checked the map there is a significant archipelagic region to north, north west and east of Australia for littoral operations.

Not sure how America wants to handle the Chinese militarized islands in the South China Sea though?!

AI Generated response below (so may be some errors)

Key Differences

Mission Suitability: The Los Angeles-class is primarily focused on open-ocean operations, while the Virginia-class excels in littoral waters and supports special operations due to its “fly-by-wire” control system and features like reconfigurable torpedo rooms.

Littoral Operations: The Virginia-class is specifically designed for littoral operations, with features like a large lockout trunk for divers and special force support.

Weapon Systems: Both classes carry Tomahawk cruise missiles and torpedoes, but the Virginia-class has more advanced vertical launch systems and payload capacity, including the Virginia Payload Module (VPM) for future off-board payloads.

Design: The Virginia-class features a different hull form, photonics masts instead of periscopes, and a relocated control room, which enhances situational awareness for the commanding officer.

Quietness: The Virginia-class is designed to be quieter than the Los Angeles-class, with a focus on reducing noise and improving its overall acoustic signature.

Virginia-class Enhancements: Littoral Capabilities: The Virginia-class is designed to operate effectively in shallow waters and coastal areas, including support for special operations forces.

Advanced Weaponry: The Virginia-class has more advanced vertical launch systems and payload capacity, enabling it to carry and launch a wider variety of weapons and payloads.

Quiet Operation: The Virginia-class is designed to be quieter than the Los Angeles-class, making it a more stealthy platform.

Special Operations Support: The Virginia-class has features to support special operations, including a reconfigurable torpedo room, a large lockout trunk, and the ability to carry unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs) and special force delivery vehicles.

Natalie – Some points of discussion:

A) There will never be a time when Australia is operating 3 submarine classes at once. By the time AUKUS-SSN is in service the Collins will either have been retired or lie hull-crushed at the bottom of the ocean.

B) Given the UK’s record on building Astute and now Dreadnaught, don’t hold your breathe that the UK will bring AUKUS in on time, budget or even at all. You are much more likely to see Australia continue to add Virginia to it’s fleet and eventually SSN-X which may be rolled into a true SSN-AUKUS vs current SSN-AUK.

C) Given the UK is having trouble keeping just one of it’s 7 Astute-SSNs at sea, don’t count on one being continually rotated to HMAS Stirling. At best it will do an annual “Fly The Flag” trip.

D) I am not sure where you are getting the 2043 date for the East Coast SSN Base. That may be a fiction of the labor government, but was not part of the original agreement where it was to be constructed straight away (you may recall then Defense Minister Peter Dutton wanting to announce the location before the election).

There is an Option 4 – Rather than further deplete it’s Virginia Fleet, the US may offer RAN, say 8 of the retiring Los Angeles Class SSN’s with a “Super-LOTE”. This would effectively fit out the Los Angeles hull with Virginia weapons, equipment, Pump Jet Propulsor (vs propellor), Conformal Acoustic Velocity Sonar (along the hull) and a new SG9 reactor from the Virginia (vs the current SG6). The virtually free hull would give faster availability and lower cost., allowing the originally planned 8 – numbers count. If and when AUKUS-SSN arrives, they would be ready to retire.

There is Option 5 – with a SSN starved USN, America lets has the RAAF take on the long range strike role by selling Australia 16 to 24 x B-21 bombers (at say 2/year). Each of which can deliver 8 long range land-attack, anti-ship and anti-air and anti-missile cruise missiles (vs the Virginia block I to IV’s 12 missiles) not just to the Chinese coast but inland including via Myanmar …. and then come back tomorrow and do it again.

Either way we need a nuclear option to deal with threats, and as US nuclear forces are spread thinly across combatant commands and being modernised.

In the future, the US will most likely need more nuclear-armed allies. Otherwise, the US will face several nuclear armed adversaries alone, which will be destabilizing.

In the shortness of time — Option 3 is the easiest to implement, but could leave Australia with a gap in its ability to conduct sovereign submarine operations.

Option 2 is a preferred option to trigger the formation of lean Indo-Pacific nuclear alliance.

Option 1 does degrade US extended nuclear deterrence, especially as US nuclear forces are concurrently undergoing modernisation. A flexible regional response is likely to alleviate some of those gaps.

US END is the status quo for Australia, so to rule out rotational nuclear-armed submarines doesn’t make any sense if we are happy to have nuclear-capable bombers land here. There is even fear here in Australia of nuclear-armed submarines turning up, due to a lack of public and even some government (amongst the public service) understanding of US END and the concept of “don’t ask, don’t tell”.

There’s also the fact that Australia has a work, health and safety culture now where we would expect to have the appropriate facilities, training and safeguards in place to deal with nuclear assets and or any accidents. From what I have googled, Australia just had some Geiger counters back in the day.

Wow. This analysis is both comprehensive and accessible, offering a clear exploration of the geopolitical dynamics at play, including the challenges posed by Russian and Chinese rhetoric and the strategic necessity of flexible deterrence options. Discussion of the three potential options for Australia’s submarine acquisition under AUKUS is particularly compelling, providing a balanced perspective on the trade-offs and long-term benefits for US, UK, and Australian undersea capabilities.

I’m curious, which of the 3 does the author anticipate this administration to choose? If you were a senior cabinet member or advisor, what’s your recommendation?

Outstanding article.