After a relatively easy advance through the southern and central parts of Libya, the country’s renegade general now has the capital in his sights.

Up until the Libyan National Army (LNA) reached the southern outskirts of Tripoli, the campaign somewhat resembled a sneak attack. The LNA is lead by General Khalifa Haftar, an ex-Libyan Army officer who served under Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi. From 1990 to 2011, Haftar lived in exile in the United States, returning to Libya in 2011 during the country’s revolution, holding a senior position in the group that overthrew Gaddafi’s regime.

In Haftar’s rhetoric, the assault is described merely as a campaign to liberate the capital from the extremist Islamic groups governing it. These assertions do have some logic to them, apart from the fact that the purported extremist groups aren’t overtly specified. Nevertheless, attempting to capture the capital—let alone effectively administering the country after a victory—may prove to be a bridge too far.

General Haftar Gains Ground

Ever since the chaotic events of 2011, Haftar has nearly continuously fought against jihadists, managing to achieve significant territorial gains. In earlier campaigns, some of his troops are known to have committed war crimes, but it would be a fallacy to assume no such crimes were committed by extremist groups on the opposing side.

Since the fall from power and subsequent death of Muammar al-Gaddafi in late 2011, Libya has lacked an effective central government. After a transition period, elections were held in 2012, which resulted in violence and left the country without functioning state organs. Concurrently, as an interim governing authority was established in Tripoli, Haftar struck an alliance with the rival governing body, the House of Representatives in Tobruk, Libya.

The legitimacy of the Tobruk-based government is itself disputed. Initially, it was recognized by the West, most likely in the hope that it would ultimately unite with the Tripoli-based government. This optimism could be deemed naïve, especially after Haftar quickly managed to mobilize an army (the Libyan National Army) primarily from Gaddafi-era officers and soldiers, with support from Egypt and the United Arab Emirates. The LNA succeeded in capturing various cities in Eastern Libya, including Benghazi, after defeating ISIS and Shura Council forces in 2017.

After gaining power over Libya’s vital oil production areas in 2016, Haftar temporarily lost the key export ports of Brega, Es Sidr, and Ras Lanuf, but was able to reestablish control over them shortly after that. In contrast to their successes in eastern Libya, Haftar and his allies lost control over Tripoli’s international airport in 2014. However, heavy fighting damaged the airport’s facilities—if not even ruined them—rendering the airport inoperable.

In the wake of these clashes, Misrata-led armed groups and their allies formed the “Libya Dawn” coalition and took over the capital. In December 2015, Libya’s two main rivals—the House of Representatives and the Tripoli-based Libya Dawn coalition—reached an agreement over the formation of a UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA), which was formed in Spring 2016.

Clashing Congressmen in the Capital

The supreme authority in Tripoli is the Presidential Council (PC), made up of nine members and chaired by the prime minister. Some members of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives never accepted the idea of a GNA, leaving little chance for any future cooperation. This is unsurprising, however, given that in any merger, members of both power centers would lose standing relative to their current positions.

Notably, the head of the GNA—Fayez Al-Sarraj—was a member of the House of Representatives in Tobruk. Regardless, this detail never fostered trust between the rival factions, nor did it prevent Haftar from seizing valuable oil installations in southern Libya. Initially occupied by armed clans and militant groups, the GNA had to send troops to protect these facilities from Haftar’s advancing forces.

On the other hand, Haftar isn’t the only one causing gray hairs for Libya’s newly formed state institutions. Basing its mandate on the General National Congress elections of 2012, the Government of National Salvation of Khalifa Ghwell was also founded in Tripoli, though without any real governing structures. In 2016, Ghwell again tried to reassert his position but failed. The following year, he and his troops were finally ousted from the capital. Even though Ghwell’s possibilities were limited, the intra-Tripoli clashes 2016–2017 challenged Al-Sarraj’s regime, and in turn, provided momentum for Haftar to slowly approach the capital.

It is likely that internal rivalries existed amongst decision-makers in Tobruk, and that Al-Sarraj was expected to loyally support the aims of the eastern Libya-based House of Representatives. Instead, in the eyes of his former colleagues, he became too independent and powerful through his apparatus in Tripoli, which led to open confrontation between rival factions.

Despite any doubts held concerning Al-Sarraj’s loyalty, not all parliamentarians in Tobruk supported Haftar’s final push towards Tripoli. Dozens pledged their support for the general, but a number rejected the use of force and urged their colleagues to convene and elect a new chairperson. Those dissenting viewed the incumbent as a close ally of Haftar, but failed to gather the necessary quorum to hold a vote until later, but were unable to effectuate any meaningful action.

Foreign Friends & Funding

Despite sharp divisions between those allied with him, Haftar had no problem commencing his campaign to seize Tripoli. When Haftar ordered his troops to “liberate” Tripoli on April 4, 2019, he had already secured Saudi-Arabian backing as well as support from Egypt and the UAE. GNA forces shot down UAVs that were reported to be of Emirati origin, even though the UAE was not officially involved. Furthermore, it is likely that Saudi funding financed the Tripoli campaign, including pay for soldiers.

On the surface, it would seem paradoxical that Haftar—a man whose stated purpose is combating extremism—is funded by Saudi Arabia’s Wahabbi monarchy. However, considering that Libyan extremists mainly subscribe to a different strain of Islamic fundamentalism than the Saudis, the paradox is not so striking. Turkey, a major regional rival of the Saudis, has provided support and backing to Al-Sarraj and wasted no time in denouncing Haftar’s move against Tripoli. Ankara has also been accused of transporting fundamentalist militants to Libya from areas that were formerly controlled by ISIS, and more recently, of arming GNA forces.

Fervent Egyptian support for Haftar is similarly complex. President Al-Sisi has taken a hard line against Islamist movements—notably the Muslim Brotherhood—but such predilections have yet to deter Egyptian participation in a Saudi-funded operation. From Cairo’s perspective, ensuring extremist groups stay away from Egypt and its vicinity is a goal that justifies even minor procedural deviations.

Similarly, French decision-making is heavily guided by security concerns. France’s strategy of ambiguity, however, merits some explanation. In 2011, airstrikes carried out by French fighter jets, alongside British and U.S. planes, were instrumental in ousting Gaddafi. Shortly after that, however, Paris began to support Haftar’s campaign against militant fundamentalists in Libya. France vetoed a UN Security Council resolution over Libya’s current situation, which was perceived as too unilaterally condemning of Haftar, illustrating France’s pragmatic approach.

More recently and in a logical continuation of its strategic ambiguity, France called on the UN Security Council to facilitate a settlement in Libya. After Al-Sarraj threatened western energy companies operating in Libya over the status of their operating licenses, France relaxed its seemingly supportive stance towards Haftar’s LNA. While exhibiting sympathy for the endangered GNA in Tripoli, as well as a willingness to serve as an intermediary, Paris is increasingly aware that it’s unlikely a negotiated settlement will be reached.

Al-Sarraj’s threat similarly applies to Italian firms. While the Italian government has held meetings with representatives of both sides, it has mostly limited itself to rhetorically highlighting the need for a political solution to the conflict. While Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s position as the head of a populist left- and right-wing populist governing coalition is a question in-and-of-itself, the primary reason for the Italian government’s intransigence is likely the ongoing refugee crisis. Italy has been a prime destination for migrants setting off from the Libyan coast, and is, rather cynically, weighing which of the warring parties is best-positioned to stem (if not stop entirely) the substantial influx.

In contrast, Libya’s neighbor Tunisia is not so concerned about possible refugees, not least because Haftar controls most of the Libyan side of the Libyan-Tunisian border. If allegations of Tunisian arms sent to Tripoli and fighters joining GNA are true, Tunis may have lost one income source. Still, a humanitarian catastrophe next door would cause significant economic and social problems for Tunisia as well.

For its part, Russia denies involvement in the escalation in Libya. In the past, Moscow has provided Haftar’s forces with arms, and Russian private security firms have reportedly been engaged in operations within Libya. The Kremlin, however, is more focused on the international legal precedents that would be established in the event of a UN-brokered settlement, so as to be able to later refer to it as a model for resolving internal conflicts. If Western powers—mainly the U.S., France, Britain, and Germany—agree to a UN-brokered settlement, the precedent established in Libya could be used by Moscow to settle, on its own terms, internal conflicts it has provoked through the creation of quasi-states like Transnistria, Abkhazia, and the Donetsk People’s Republic, to name a few.

Haftar advances towards Tripoli

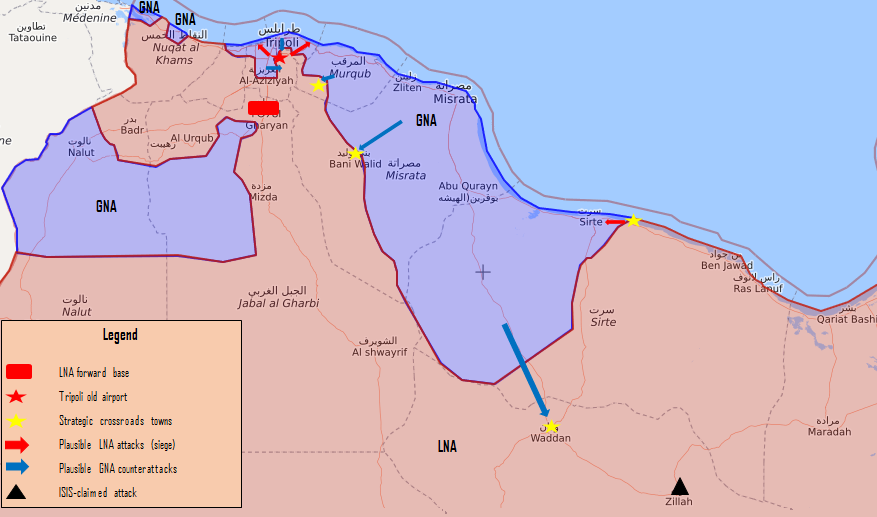

As the UN voiced its concern over impending hostilities— in vain—Haftar’s forces closed in on the capital along the two main roads that run parallel to one another into Tripoli. The initial phase was rather quick, and Haftar’s troops succeeded in advancing to the Tunisian border in the west and Janzur on the western outskirts of Tripoli, essentially cutting the city off from any supplies or reinforcements, leaving just two small GNA-loyal pockets along the coast. In the opposite direction, this also prevents possible refugees from crossing over to Tunisia.

Shortly after that, the LNA lost one airplane, reportedly due to technical failures. The LNA bombed the city’s only functioning airport, Mitiga, which was closed for several days. Once again, the heaviest fighting has been concentrated in and around the old airport, located roughly 30 kilometers south of the city center. For now, Haftar is in control the airport itself, with enemy forces just yards away.

Situated between the two main roads leading to Tripoli from the south, the airport serves as a crucial foothold to block access to the city, as well as a forward base from which to conduct further operations. Together with Janzur (had its capture succeeded—instead, around 140 of Haftar’s men were besieged and captured) and a strategic intersection close to the suburb of Tajoura, these gains would offer optimal positions from which to lay siege to the city. Or, if the LNA manages to establish a hold on the old airport, Janzur isn’t even needed, since the LNA already controls Surman, which blockades the area west of Al-Zawiyah.

As of this article’s publication, the LNA’s main base of operations remains in Gharyan, some 60 kilometers from Tripoli, whereas the frontline goes from the Qaser Bin Ghashir suburb adjacent to the old airport. Gharyan itself closes a counterattack route via Kilka—the corner of the vast GNA-loyal enclave situated behind the LNA—just southwest of Tripoli. The LNA’s loss of Al-Aziziyah was a setback, and fierce fighting continues around it and the old airport. The LNA has managed to achieve minor territorial gains around Al-Aziziyah, and for a short period, were able to progress to the Tripoli Medical Center, roughly 10 kilometers from the city center.

Overall, the LNA has been unable to break through the Tripoli defense lines, which have been reinforced by fighters from Misrata. If Haftar were to concentrate all his forces in Tripoli, it would weaken his flanks, leaving his positions open to a possible counterattack from Misrata—towards Bani Walid or from along the eastern coast. Conversely, by drawing in and binding as many Misrata-based armed groups as possible to the Tripoli trenches, Haftar diminishes the likelihood of a counterattack from Misrata.

Launching an assault on a new front along the coast by Sirte is another tactic Haftar could employ to prevent any attacks on his forces from the rear. On the other hand, however, it implies that breaking through Tripoli’s southern defenses proved harder than initially expected. Thus, clashes remain sporadic, but increasingly heavy shelling has inflicted large amounts of damage on the southern Tripoli suburbs, as thousands have fled amidst a death toll that has risen into the hundreds. Even if the fighting remains localized, the situation could worsen quickly. With deteriorating living conditions, there is a risk of a far greater humanitarian crisis.

No easy solution

Escalation into a full-scale civil war cannot be excluded, given the aspirations of the involved parties. As the capital plays a strategic role, capturing it would solidify—to an extent—Haftar’s control over Libya. Nevertheless, maintaining control over crossroad towns such as Tarhouna, Bani Walid, Waddan, and a small village east of Sirte remains vital for LNA operations in the northwest of Libya.

On the other hand, Al-Sarraj’s most effective (and likely only) way to remain in power is to defeat Haftar’s LNA at Tripoli’s gates. A counterattack from Misrata or anywhere else would bog down forces plus weaken the capital’s southern defenses. Thus, the GNA’s primary objective is ensuring that the main routes into Tripoli remain closed to the LNA to preclude the possibility of a siege on the city.

In the event of an all-out civil war, there would be no victors. First and foremost, the death toll would likely rise into the tens of thousands, and it would take substantial time and resources to rebuild Libya after another civil war. Hafter can’t afford to lose the battle for Tripoli, as it would mean the end of his career. If Haftar is victorious, the population of Tripoli isn’t likely to welcome him as a liberator, thus forcing him into a long campaign to win their hearts and minds.

Likewise, if the GNA prevails, it cannot be sure whether the various armed groups backing it now would subsequently submit to its authority. This would be particularly so if the decisive factor delivering the victory were troops from Misrata, who might seek a more significant share of power, encouraged by their successes and perceived leverage. In this scenario, the intra-Tripoli situation from 2016-2017 would likely repeat itself. Furthermore, several armed groups remain, among whom are former ISIS militants, who could take advantage of factional infighting. Such groups are unlikely to submit to the rule of a central governing authority, and whoever should prevail in Tripoli must effectively deal with these factions—or else the next conflict is already looming.