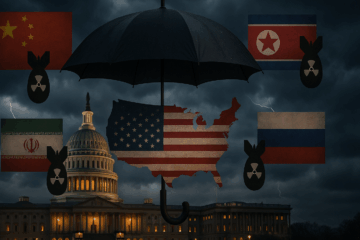

Global arms control regimes are built on the pillars of trust, dialogue, transparency, mutual respect, restraint, verification, and, most critically, consensus among great powers. However, leadership in this domain risks deterioration at a time when the world urgently needs a renewed commitment to peace and stability.

As great powers become entangled in trade disputes, the spillover effects threaten to undermine the cooperative spirit essential for effective arms control. These economic conflicts erode bilateral relationships, making it even more challenging to negotiate future agreements on critical and emerging domains such as artificial intelligence, cyber warfare, and the militarization of outer space.

Tariffs can disrupt trade, increase prices, stifle innovation, and agitate the supply chain. Moreover, it can weaken American global leadership as long-term allies face an American president unwilling to accept high tariffs on American exports while guaranteeing low tariffs on imports. American efforts to counter China are disrupted by tariff disputes as well, as allies and foes coordinate their strategies for countering President Trump’s effort to reduce tariffs on American exports. The president’s actions erode the confidence of allies in extended nuclear deterrence because allies begin to question whether the United States will continue to subsidize security, if they are demanding an end to protective tariffs.

The tariff dispute between China and the US, two large trading partners, severely affects arms control and strategic stability. It exacerbates crisis, heightens mistrust, undermines confidence-building measures, and curtails the possibility of a constructive arms control framework. It is, however, not unexpected. The United States long tolerated protective tariffs and poor intellectual property protections by the Chinese. Thus, rebalancing should not come as any surprise, even if it is disconcerting.

American technological superiority, innovation, cutting-edge military and civilian technology, and significant soft-power influence are the key components of its hegemonic status. Central to this dominance is access to rare earth minerals, which are critical for producing advanced weaponry, including missiles, drones, artificial intelligence (AI)–driven systems, and cutting-edge civilian technologies. However, the US faces a growing vulnerability in this domain, as China currently controls approximately 70 percent of the global supply of rare earth elements. This strategic dependency seriously challenges American innovation and military effectiveness.

However, the American military is already in decline according to a report from the US Army Science Board, which reveals the limitations of the American industrial base. The report warned that the US may be “incapable of meeting the munitions demand created by a potential future fight against a peer adversary.”

The conflict in Ukraine underscores this concern, as the US struggles to maintain adequate production levels of artillery shells, drones, rockets, and missiles primarily due to insufficient stockpiles of critical components. Furthermore, structural deficiencies are increasingly evident within the US Navy. As of 2023, less than 68 percent of surface fleet ships were rated “mission-capable,” with only 63 percent of attack submarines meeting the same standard. Compounding these challenges, American shipyards are currently unable to produce more than three destroyers annually. By contrast, China possesses 13 shipyards capable of constructing large and deep-draft vessels one of which reportedly surpasses the entire US shipbuilding capacity.

The ongoing US-China tariff dispute reflects a zero-sum strategic mindset, intensifying hostilities and reducing incentives for restraint or cooperation. This economic confrontation has already narrowed the space for meaningful arms control dialogue. The imposition of sanctions on each other’s officials and entities alongside increasingly provocative rhetoric from senior officials risks further erosions of the fragile trust necessary for future diplomatic engagement, particularly in arms control and emerging domains such as AI, cyber warfare, and outer space.

Traditionally, China rejects arms control as the US had far more weapons than China. Tarriff disputes reinforce the narrative that the US is using economic means to contain China’s rise, making China less likely to engage in future arms control discussions. Moreover, diplomatic relations and multilateralism will weaken and increase mistrust—leaving no room for constructive future arms control talks.

Arms control forums are increasingly fragile as mutual trust and respect for arms control and disarmament among the great powers declines. Tariff disputes create mistrust, which complicates the verification process, and the supply chain supporting the global cooperative arms control verification limits the ability to enforce or verify compliance with arms control agreements.

Trade disputes deepen mistrust and normalize confrontation over cooperation, secrecy over transparency, and arms racing over arms control. This leads to proliferation while making accountability less relative and paves the way for a fragmented world order with little or no hope for future arms control.

Moreover, it increases the chances future administrations face a backlash for rolling back policies that demand equitable treatment of American trade goods, fearing internal backlash for being soft on China. This will permanently lock both states into an adversarial stance, reducing any flexibility in arms control. Moreover, if the US wants to reconsider any future arms control discussion, political costs may prove too high, leaving fewer options to prevent an arms race.

In 2019, President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, after Russian cheating became too hard to ignore. Meanwhile, the future of New START remains uncertain and fragile.

At such a critical juncture, President Trump’s demand that American exports sent to foreign markets receive equal treatment to those foreign imports entering the United States, penalizing both allies and adversaries who enact punitive tariffs, may be unsettling for recipients of increased tariffs, but it should come as no surprise that an American president elected to stop the outflow of American wealth would seek equal treatment for American exports.

Many Americans are willing to see the subsidies to foreign nations—that are brought about by high tariffs on American exports and American extended deterrence—come to an end. This may lead to an erosion of confidence in American benevolence by some states.

South Korea, for example, was shocked that the United States took offense to the very protectionist policies that allowed South Korea to become the third largest auto producer in the United States, all while effectively preventing American automobile sales in South Korea. Thus, South Korea is reconsidering their non-nuclear status and exploring an independent nuclear deterrent. As President Trump seeks to level the playing field by forcing down the tariffs of trade partners, under the threat of higher tariffs on imported goods, allies should come to understand that the United States is increasingly unwilling to subsidize others. While this may be a jarring fact, it is not a purposeful effort to destabilize arms control.

Thus, trade disputes may cause allies and adversaries to reconsider American willingness to accept unequal trade and disproportionate burden sharing. In the long run, equilibrium will return. It is just a matter of what that equilibrium may look like.

Muhammad Shahzad Akram is a Research Officer at the Center for International Strategic Studies, Azad Jammu Kashmir. He holds an MPhil in International Relations from Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. He is an alumnus of the Near East South Asia (NESA) Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University (NDU), Washington, DC. His expertise includes cyber warfare and strategy, arms control, and disarmament.