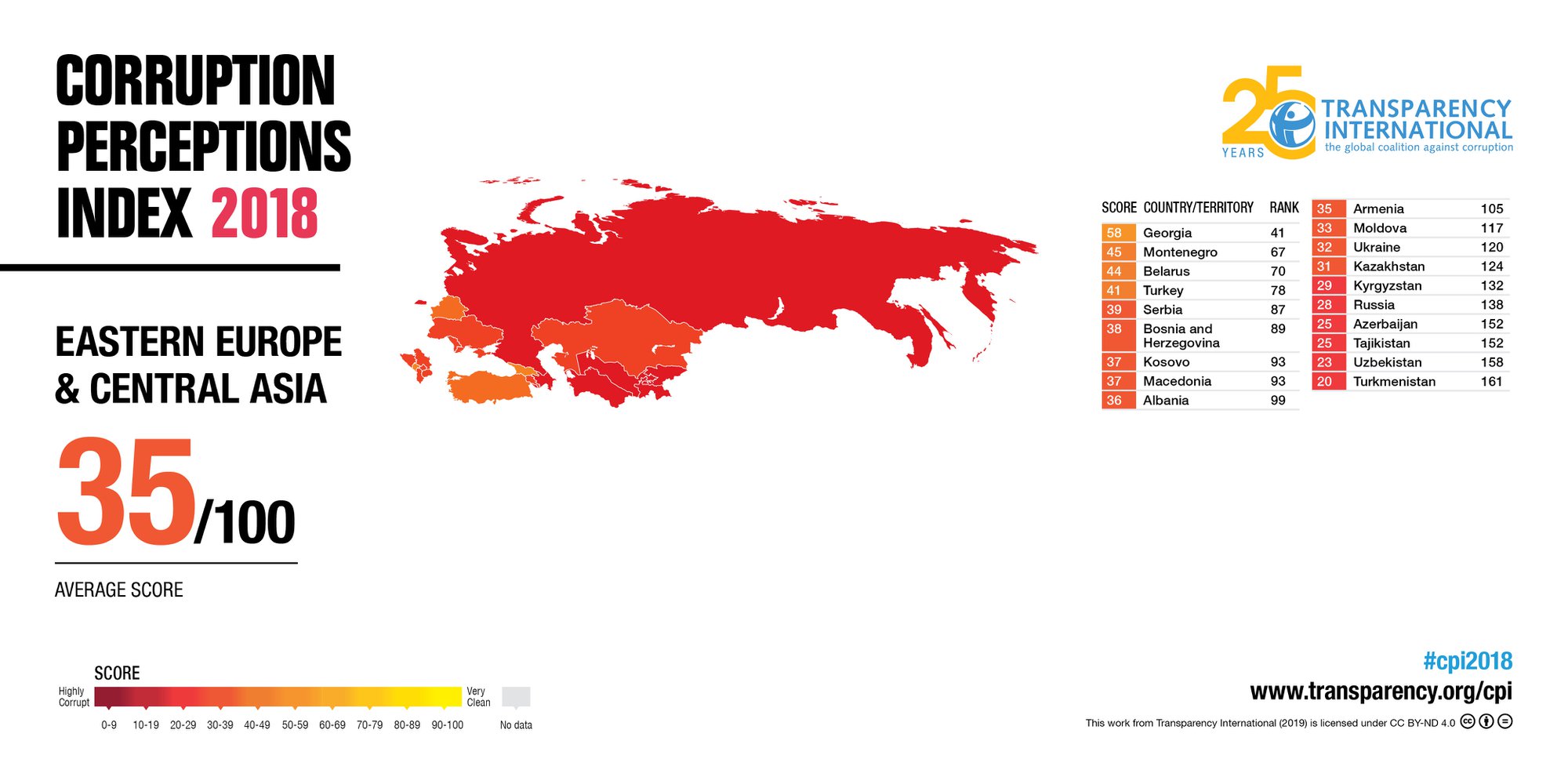

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), corruption appears to be on the rise in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. To the well-read citizen, this is not surprising.

Reports of Ukrainian state capture, Russian corruption, and bribery in other Eastern European and Central Asian states are on the rise. In all of the countries survey, only one country scores over 50 out of 100 points, with the average of countries only averaging a score of 35.

What’s the relationship between corruption and security?

Corruption undermines democratic consolidation and leads to voter disenfranchisement. This results in an overall lack of political will to combat illicit behavior in the public sector. In many Eastern European countries, history has provided few institutional checks and balances.

According to Transparency International, “one of the biggest impediments to fighting corruption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia is state capture, where powerful individuals or groups seize control of national decision-making and use corrupt means to circumvent justice.”

It is unlikely that Eurasia will see widespread democratic stability in the near future, with countries like Azerbaijan (scoring 25), Russia (28), Kazakhstan (31), Kosovo (37), Serbia (39), and Montenegro (45) dropping in rank or continuing to stagnate.

While there are exceptions such as Ukraine’s increase from 30 in 2017 to 32 in 2018, given Ukraine’s weak enforcement of anti-corruption reforms enacted in 2014, any improvement is more superficial than it is long-lasting.

What’s wrong with the status quo?

For many, state capture and corruption have been everyday factors of life for the past two decades. Some see the status quo as essential for maintaining stability. Implementing a more equitable system carries a host of risks—from public trials to long-term imprisonment. For many in the ruling class, retaining current systems of informal governance seemingly carries zero cost.

However, the populist wave of 2018 might say otherwise. As voter frustration with corruption continues to rise, so too will their impatience with those currently in power. Leaders that rode those waves of anti-corruption legislation—such as Armenia’s Nikol Pashinyan—must now follow through on their campaign promises, lest they risk being thrown out themselves.

Even countries like Russia, which have more entrenched systems of corruption, are beginning to see popular discontent. According to Russian’s Public Opinion Research Center, trust in Russian President Vladimir Putin has fallen to an all-time low since 2006.

While much of this can be attributed to Russia’s aggressive foreign policy in Ukraine and Syria, observers must also take into account public disapproval over an increase in the retirement age and growing frustration with U.S. and European sanctions.

Corruption isn’t just a domestic concern—the extent to which corruption dictates domestic policies inherently affects domestic and regional stability and security. Therefore, endemic corruption in Eastern Europe and Central Asia doesn’t bode well for democratic cohesion and international support for human rights.