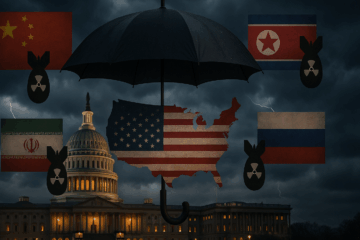

The world is entering a new era of nuclear disorder. This new era is characterized by several elements. They include the breakdown of nuclear (and conventional) arms control, the return of superpower competition, the return of conventional war, the normalisation of nuclear threats in both Europe and the Asia-Pacific, the rapid growth of Chinese and North Korean nuclear arsenals, and ongoing military modernization in the region.

A decade ago, Paul Bracken warned of such possibilities in his book, The Second Nuclear Age. Because deterrence theory went out of vogue for so long in the West, analysts are now woefully unprepared to think about these challenges and their implications. Today, all possible threats to our Western notions of peace and stability have been jumbled into one giant intellectual recycling bin of deterrence theory. It is time to talk much more seriously about (1) the role of nuclear weapons in deterrence and (2) the role of nuclear deterrence in a new era of nuclear disorder in the Asia-Pacific.

Nuclear weapons play a unique and unprecedented role in how nations think about geopolitical order. They have fundamentally altered how countries think about alliances and the nature of international order. William Walker wrote about the establishment, in the late 1960s, of a nuclear order based on managed systems of deterrence and abstinence. The former was a system “whereby a recognized set of states would continue using nuclear weapons to prevent war and maintain stability, but in a manner that was increasingly controlled and rule-bound,” and in which there was a degree of familiarity in essentially dyadic deterrence relationships.

Nuclear abstinence consisted of a system “whereby other states give up sovereign rights to develop, hold, and use such weapons in return for economic, security, and other benefits,” concomitantly with the provision of nuclear umbrellas and a stable Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). It is a system whereby not only the possession, but also the use of nuclear weapons is controlled. According to Walker, the stability and robustness of these two systems would provide the rationale for many states in the international system to abstain from acquiring weapons and for states to rely on the US for their national survival.

There are several elements that gradually developed after the second world war that characterized this nuclear order—dissuading countries from developing nuclear weapons. First, the number of nuclear weapon states is relatively small. Second, nuclear weapons are no longer considered merely bigger and better conventional weapons. Third, there are strong norms against possession and the use of nuclear weapons. Fourth, there are no direct and immediate military threats to US allies. Fifth, war between major powers is relatively unlikely.

This and the prospects for nuclear proliferation are relatively limited. The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) proposed in the late 1960s eventually attract more and more states, thus contributing to a norm against nuclear proliferation. It also contributed to nuclear and conventional arms control as concepts and policies in the international community. The world was able to more easily navigate crises and confrontations as thinking evolved about strategic theory and concepts and their application to real world politics and diplomacy.

The international (nuclear) order held together. It is now slowly eroding. China is modernizing its conventional and nuclear forces, all while growing increasingly bellicose and regularly threatening to invade Taiwan.

Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. The West did nothing and never imagined this would be followed by a full-scale invasion eight years later—with regular Russian threats to use nuclear weapons.

Now, Australian academic Peter Layton is writing about “this nuclear threat business.” Until recently, this behavior was reserved for rogue states like North Korea. Such behavior was beneath great powers such as Russia and the United States. Not only does the West have to think about deterrence in a multipolar setting, but it must face nuclear dictators.

Nuclear arsenals in Asia are also expanding. From China’s rapid nuclear expansion to questions about the future of Pakistan’s nuclear posture, the future is uncertain. There are renewed questions about the future of South Korea and nuclear weapons.

Arms control is also breaking down. Much to the chagrin of arms control careerists, who argue for unilateral, bilateral, and trilateral nuclear arms control as a public good sui generis, arms control is not carrying the day. Bereft of the intellectual foundations of deterrence that guided impressive negotiations in SALT I and II, and even START I, discussing nuclear strategy is now taboo in the West.

The nuclear order that existed during the Cold War and the post–Cold War peace dividend, especially in the Asia-Pacific, is eroding rapidly. For many nuclear historians, this trend is not new. Now is the time to grieve the loss of the utopian dream and think seriously about how to navigate this new era of disorder and the role of nuclear weapons in deterring war and promoting peace.

Christine Leah, PhD, is a Fellow at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies. Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

About the Author

Christine M. Leah

Dr. Christine Leah is a Fellow at the US National Institute for Deterrence Studies and has worked on nuclear issues at Yale, MIT, and RAND and in London, Singapore, and Canberra. She is the author ofThe Consequences of American Nuclear DisarmamentandAustralia and the Bomb.

Christine Leah’s article is excellent and thought provoking. The US’s and our many allies’ and friends’ nuclear deterrence experts, both in and out of military service — including NIDS researchers worldwide — have been working hard on exactly the challenges that she enumerates, for several years (or much longer). Great progress is being made, but make no mistake that terrifically challenging work still lies ahead. One key is to not just rehash or reinvent deterrence theories from way back in the First Cold War, since global geostrategic conditions are now so very different, as are advanced weapons technologies. Peace Through Strength remains the very essence of effective deterrence, including especially nuclear deterrence. America’s nuclear deterrence systems modernization programs must continue with the greatest speed and efficiency. The enhancements and streamlining to U.S. federal systems, and to the defense industrial base, currently underway, are absolutely vital and require the utmost priority, commitment, discipline, inventiveness, and timeliness from everyone involved. THINK DETERRENCE!