China learned the value of hard power during its so-called “century of humiliation.” Now, as China begins its century of expansion, it’s learning to use soft power, too.

In reference to China’s foreign policy strategy, Deng Xiaoping once said: “hide your strength, bide your time.” For three decades, Chinese foreign policy was implemented accordingly. As China realigned itself as a market economy, it seemed content in its role as the “world’s factory;” at the same time, the rest of the world was content with cheap consumer goods that were produced in China.

In recent years, however, Xi Jinping has overseen a significant shift in China’s foreign policy. China has become increasingly assertive in pursuit of its national security, foreign policy, and economic interests both in the Indo-Pacific region and throughout the world, from Asia to Latin America. China’s policies and behaviors, from the massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to the creation of artificial islands in the South China Sea, are clear indicators that Beijing is done hiding and biding.

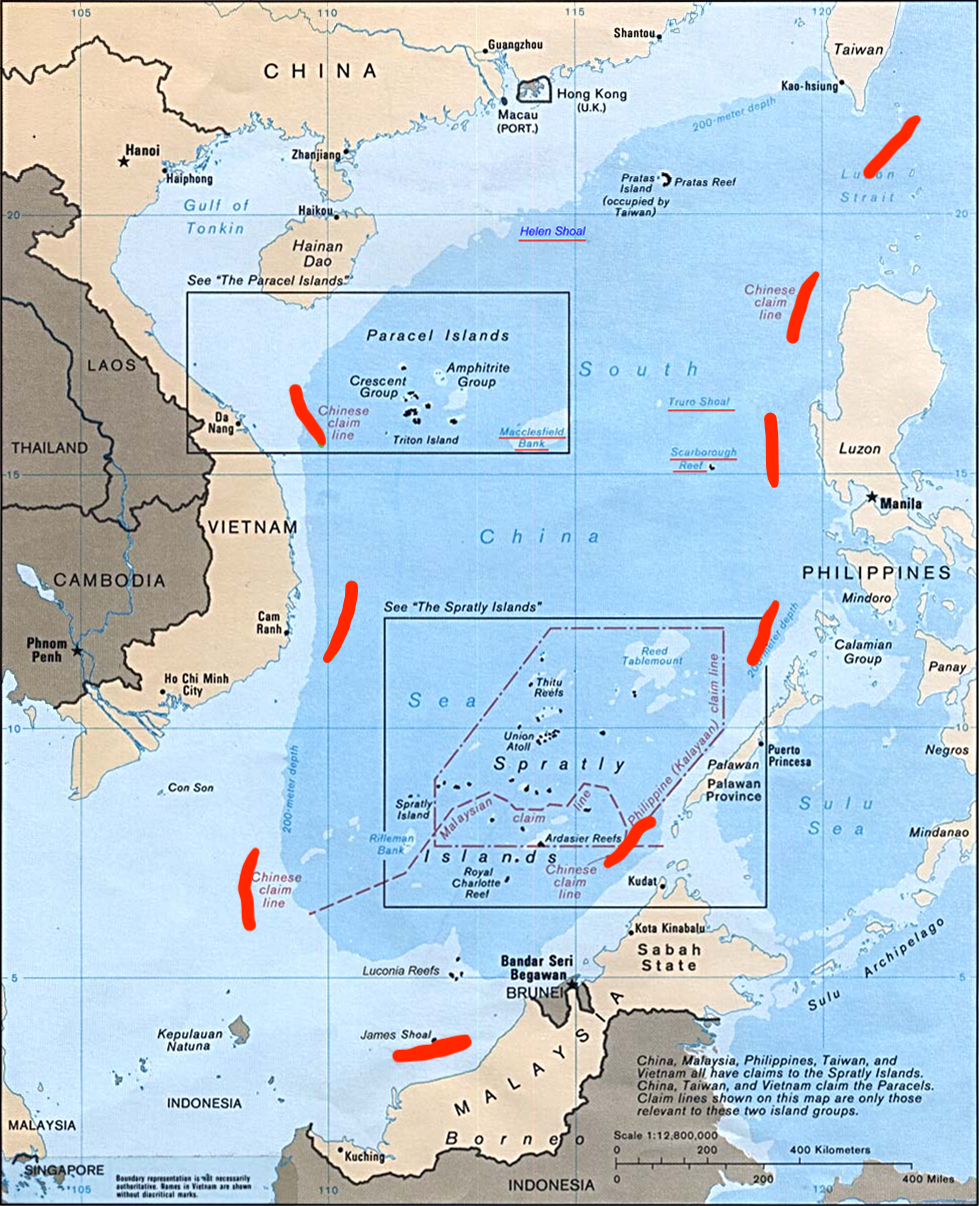

Significant amounts of natural resources and secure trade routes for exports are essential to ensure China’s continued economic growth. As the land components of the BRI expand across Central and Southeast Asia, the South China Sea remains a point of geopolitical volatility. The South China Sea is host to some of the world’s most critical shipping lanes. Eighty percent of China’s energy imports pass through the Strait of Malacca, strategically positioned between the countries of Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia—all of which are American allies.

China seeks to place the South China Sea firmly within its sphere of influence. Doing so would see China move from a position of geopolitical vulnerability to one of strength, effectively maintaining a “Great Maritime Wall” that would ensure China’s unfettered access to both the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Consolidating and solidifying its sphere of influence will be the most significant Chinese foreign policy challenge of the twenty-first century while maintaining the status quo and retaining its strategic advantage will be that of the United States.

Estimates currently project that China will be operating a fully-fledged blue-water navy by 2030. It is likely that, around this time, China will be pushing to break through the First Island Chain in the East and South China Seas that are currently controlled by U.S. allies. Until China’s hard power capabilities are fully matured, China will continue to vie for influence using diplomacy and other soft power vehicles.

China’s Soft Power Capabilities

The canonical conception of soft power is centered mainly around ideas like constitutionalism, liberal democracy, and human rights, none of which are on offer from an unapologetically authoritarian China. While Chinese universities are drawing growing levels of international students, the fact remains that, on the whole, China’s cultural pull is meager. Its most famous artist lives in exile, state media outlet Xinhua gets little traction outside of China, and while K-pop and J-pop are widely played outside of Korea and Japan respectively, Chinese popular music has failed to capture international attention.

China may not have much to offer as an alternative to the American Dream for populations around the world, but for the leaders and governments of developing states, China presents an attractive partner. Rather than seeking investment and financial support from the Bretton Woods institutions, which require governance and human rights reforms, many governments are turning to Beijing, which attaches far fewer strings.

While China’s lack of democratization does damage its international reputation, that damage must be viewed in the context of the relative decline of American soft power. The post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have harmed the global impression of the United States as a “bringer of democracy,” to the extent that such a phrase are now mostly invoked in irony.

In Latin America, the United States’ historical sphere of influence, many states are signing bilateral agreements with China on everything from hydropower projects to the development of telecommunication networks. China’s engagement in Central and South America has resulted in it becoming the region’s largest creditor. Furthermore, as U.S. levels of domestic shale production increase, there will be less U.S. demand for foreign energy. China’s thirst for oil, on the other hand, will continue unabated. For many Latin American nations, the choice of China as an economic partner has been a straightforward one.

The appeal of China as an alternative isn’t due to Beijing’s alignment with specific ideological criteria. Instead, China is appealing because it is an alternative. China profits from the extent to which the U.S. influence declines relative to its own, not from the gravitational pull of some cultural or ideological preponderance. This means that even those pursuing Western-style governance structures will see opportunities to engage with China. For these countries, if the United States won’t purchase foreign oil, or the World Bank won’t fund a development project, China will.

China’s Carrot and Stick

The allure of the Chinese alternative is visible in the South China Sea also. In this rather authoritarian region, liberal democratic values are held in lower regard than economic prosperity and political stability. Singapore stands as a shining example that liberalism is not a prerequisite for success in these metrics. To a working class citizen in an underdeveloped province of Indonesia or the Philippines, democracy—or “democrazy” as it is sometimes termed in the region—can seem stultified and inefficient. China, as it would have the world believe, has demonstrated that its model for global engagement achieves results.

China has attempted to satisfy concerns about the nature of its investment and economic policies. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, founded and led by China, is an attempt to increase engagement with countries in the Indo-Pacific region. The AIIB is a signal to countries in the region that Chinese investment isn’t solely for Latin America or Africa. Furthermore, China has been willing to engage in multilateral forums and agreements as it tries to convince its neighbors that its intentions are benign.

However, Beijing has mostly failed in this regard. Chinese military activity has increased in the South China Sea. China’s naval presence in the region has increased dramatically; the Chinese Coast Guard has even escorted fishing trawlers into Indonesian waters. Beijing is working diligently—and successfully—to reduce Taiwan’s international relations. The Nine-Dash Line (which outlines China’s South China Sea claims) continues to be a significant source of tension; the region is flush with complex, multilateral territorial disputes, any of which could erupt into conflict with little warning.

China, for its part, never intended to assuage its neighbors’ concerns completely. Instead, China is trying to show that, while it carries a big stick, it can be reasoned with.

Indo-Pacific states are now engaged in a continuous balancing act. Each country is weighing the benefits and costs of their relationship with the established superpower (the United States) against the incipient one (China). While China moves towards the maturation of its hard power, it is perhaps operating within the last phase of biding its time. China has attempted to sell a narrative where it is the reliable power in the Indo-Pacific, rather than a country several thousand miles across the Pacific, from which the echoes of “America first” can be heard.

Alliances are Essential for Maintaining the Status Quo in Southeast Asia

Nevertheless, regional alignment remains with the U.S.—for now. Staring down vociferous Chinese criticism, South Korea placed an American anti-ballistic missile defense system on its soil. Taiwan continues to hedge against a Chinese threat by seeking closer ties with the U.S. as regular arms sales have resumed under the Trump administration. The U.S. has turned a blind eye to Japan’s latent nuclear capabilities and encouraged the evolution of its nominal self-defense force into something more potent.

The United States’ network of alliances in Southeast Asia is intact but fragile. The U.S. must remain credible to each state individually to be credible to all states collectively. Should the U.S. signal a lack of interest—such as by withdrawing from the TPP, publicly questioning the value of a de-facto independent Taiwan, or demonstrating a hesitation to fight alongside South Korea in a conflict with North Korea—its network of alliances may be compromised.

In the twenty-first century battle for influence in the South China Sea, credibility is everything. China currently sees what it perceives as a power vacuum, and it is only too happy to slide into it. Affirming its influence and presence in the Indo-Pacific will be a key U.S. foreign policy objective over the next century. To succeed, the U.S. must act with determination yet delicacy, so that it may maintain the network of alliances that currently safeguards a strategic advantage over an emergent China.

About the Author

Mattias Bouvin

Mattias Bouvin is an independent researcher with degrees in International Relations and Security from University College London and the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. He writes about strategy, risk, foreign policy, and energy. He is on Twitter @_mbouvin.