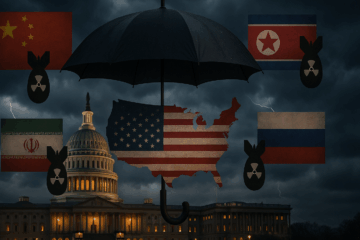

A strong nuclear deterrent reduces risks to the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Such is the view of many within the nuclear enterprise.

Arms control and disarmament advocates differ with this view, seeing the deterrent as a risk that must be reduced in size and function via various forms of diplomacy that range from one-party declarations and codes of conduct to formal arms control agreements. These sorts of undertakings are currently moribund within officialdom, though enjoying an eternal spring of hope among the single-issue think tanks, academics, and commentators who strive to sway government.

Paradoxically the current surge in hostilities between the United States and the axis of autocracy (China, North Korea, and Russia) could furnish the spark that revives official efforts at both improving deterrence and renewed arms control. For instance, an updated Budapest Memorandum might form one component of a settlement or freezing of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. An Iranian “regime change” may also offer a path for a true and verifiable non-nuclear-weapon Iran.

The modality of any future arms control arrangement could vary greatly. Not all arms control arrangements are treaties. Given the current international situation among nuclear-armed states, treaties might indeed be the least likely of modalities. Some modalities that future arms control arrangements could take include unilateral American declarations, American-backed codes of conduct, American-backed norms, agreement within NATO (such as the Committee on Proliferation or the Nuclear Planning Group), unilateral American renewal of earlier Negative Security Assurances (such as those deposited with the United Nations), bilateral or multilateral statements, bilateral or multilateral memorandum or other agreed instrument short of a treaty, and/or bilateral or multilateral treaties.

The Process of Arms Control

All these arms control approaches present challenges to American and NATO forces. They also present opportunities to refine force posture and employment options. Three concrete steps are useful in ensuring American and alliance leadership receives constant feedback with operational decision-makers.

First, it is important to sustain collaboration. As government and American allies contemplate arms control arrangements, nuclear-force commanders should offer information on the challenges and opportunities that various permutations of an arrangement present to force posture and operations. Not all ideas are operationally possible.

Second, highlight the challenges that an arrangement poses to fielded forces. As part of any discussions, commanders should relate how they would adjust operations as nascent arrangements move toward implementation. This would likely be a stepwise evolution of operations in reaction to implementation of disclosures and intrusion that could accompany various forms of arms control measures. Policymakers rarely understand what their aspirational objectives mean for operational forces.

Third, highlight opportunities an arrangement creates for forces. Similarly, commanders should monitor the evolution of arms control arrangements and be on the lookout for arrangements that permit gleaning information about adversary forces—information that is useful in crafting the best force posture, plans, and operational tactics.

These feedback loops would evolve in phases over the time that an arms control arrangement is contemplated, refined, and implemented (or rejected).

The Phases of Arms Control

Any future arms control agreement should have six phases:

Phase 1 takes place during internal American contemplation of potential arms control arrangements. Classified analysis of changes to operations that an arrangement might necessitate are discussed. When inspections are proposed, any detrimental effects to operations from various forms of inspection are discussed. Discussing the benefits of inspecting adversary installations is also an important consideration.

Phase 2 occurs during outreach with adversaries and third-country parties. Internal “food-for-thought” papers from the operational community are prepared for negotiators and strategic-communications personnel. Deliberate public statements such as editorials and conference presentations serve a useful purpose in explaining American interests.

Phase 3 takes place during formalization of an arms control arrangement. When requested by the Department of Defense, Department of State, National Security Council, the president, or other officials, public statements are made for adversary consumption.

Phase 4 is the implementation phase. This is the period in which an arms control arrangement comes into effect by treaty agreement or as a unilateral/bilateral/multilateral action. Classified reports on implementation progress of the new arrangement are prepared. When inspections are part of the arrangement, coordination between government agencies occurs.

Phase 5 is focused on sustainment. During this period an arms control arrangement is in effect. Classified reports address difficulties from the arrangement.

Phase 6 is the sunset period. This is when the arms control arrangement ends or appears to be faltering. Analysis of the operational steps, timeline, costs, equipment, and personnel necessary to terminate the arms control arrangement is conducted. Classified reports on progress toward ceasing any earlier changes to operations and capabilities, necessitated by the arrangement, are conducted.

Conclusion

Arms control for the sake of arms control was always a bad idea. The United States is no longer in a position where it can enter into arms control agreements because it furthers an idealist ambition to promote peace. Today, arms control is only useful if it furthers American interests.

Taking a hard-nosed look at arms control in its various forms is necessary, but it must be acceptable for the answer to be no. The United States is no longer in a position to act altruistically. Russia is a superior nuclear power, and China may reach a similar status within a decade. The world has changed and American leaders must accept that its adversaries are no longer willing to follow America’s lead.

Professor Stephen Cimbala, PhD, is a professor at Penn State-Brandywine. Views expressed are his own.

About the Author

Stephen Cimbala

Dr. Stephen Cimbala is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Penn State university, Brandywine. He is currently a senior fellow with the National Institute for Deterrence Studies.