In October 1964, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tested its first nuclear device at Lop Nur in China’s western Xinjiang province. Shocked by the test, Taiwan’s President Chiang Kai-shek was convinced Taiwan needed nuclear weapons.

In 1966, he directed the establishment of the military-controlled Chung Shan Institute of Science and Technology (CSIST) and made nuclear weapons research a primary focus. Over the next two decades, Taiwan aggressively pursued a clandestine nuclear weapons program. Its remarkable advancement came to an abrupt halt in 1988 because of one Taiwanese scientist who was also a Central Intelligence Agency informant. What if that had not happened?

Continuing tensions in the Taiwan Strait along with conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East have renewed conversations about the validity of the extended deterrence provided by the United States. Understandably, states may doubt the veracity of these current security guarantees.

We offer a counterfactual historical analysis to assess the traditional tradeoffs between a state’s right to nuclear weapons for security versus the established US foreign policy commitment of extended deterrence, which costs the United States significant human and material resources. If Taiwan was permitted to build a successful nuclear weapons program, what would the security environment in the Taiwan Strait look like today? Could the United States have prevented its own security dilemma with China, or would it have become more precarious? Can a what if scenario help inform a what’s next scenario for American foreign and nuclear policy?

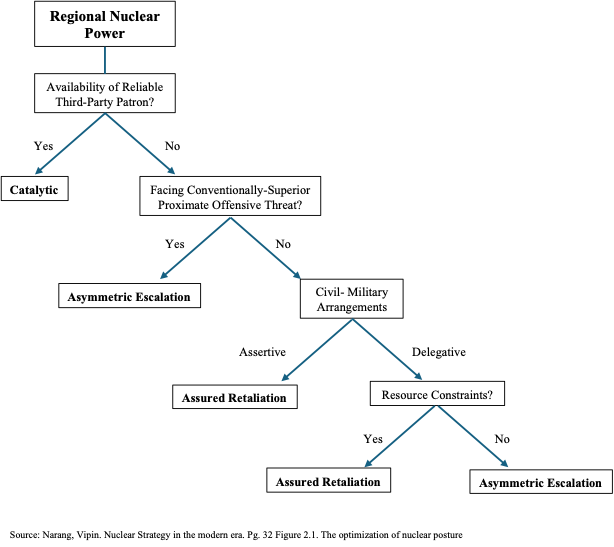

To begin the analysis, a baseline understanding of nuclear postures is needed. Vipin Narang offers a simple construct for nuclear posture. It is the combination of a state’s capabilities, employment doctrine, and its command-and-control structure.

In his book, Nuclear Strategy in the Modern Era, Narang introduces a framework that systematically explains the nuclear posture choices made by regional powers based on two variables: whether there is a third-party patron able to defend them and the proximity of a conventionally-superior threat. It then applies several unit-level variables when the security environment is indeterminate.

Moving through his decision tree (below), regional nuclear powers fall into three potential postures: catalytic, asymmetric escalation, or assured retaliation.

A catalytic posture depends on a third-party patron to intervene and de-escalate the situation before nuclear exchange happens.

An assured retaliation posture is assumed when a nation can keep its nuclear forces secure from a potential disarming first strike and assure a costly retaliation on the aggressor. An asymmetric escalation posture is designed to deter conventional attacks by credibly showing the ability and willingness to escalate to nuclear first use options at first sign of conventional attack.

With the groundwork laid, it is possible to examine the PRC’s nuclear posture and posit a hypothetical Taiwan posture. Historically, China maintained an assured retaliation posture. According to the Federation of American Scientists, by 1970, China had approximately 50 nuclear weapons and by 1980 that number was 200. It maintained a small arsenal for over 30 years while maintaining its assured retaliation posture. It was an arsenal that Taiwan could counter, if allowed to continue to build its own weapons.

There are some assumptions required to run through this historical counterfactual. First, Taiwan would have been able to start developing nuclear weapons by 1990. When program shutdown began in January of 1988, Taiwan was assessed to be “at least a year or two away from having a three to six-month breakout capability.” Second, Taiwan would have been able to match a similar pace of production that China achieved from 1964-1979.

Third, China would not have intervened militarily to dismantle Taiwan’s nuclear program. This assumption is based on protections by the United States remaining intact, creating enough deterrence at a time when the People’s Liberation Army, though nuclear capable, was relatively weak.

Fourth, the great powers would not have engaged in counterproliferation efforts against Taiwan. In reality, this was not the case.

Fifth, American concerns over political instability in Taiwan were more muted, which reality would later vindicate. Again, there were always real concerns with Taiwanese autocracy.

Accepting these assumptions and following the above framework, we suggest Taiwan could have fielded approximately 50 nuclear weapons as early as the mid-1990’s. This nuclear arsenal would have been sufficient to achieve an asymmetric escalation posture, which is best suited and specifically designed to counter conventional attacks from a conventionally superior neighbor.

To be credible, Taiwan would need to declare that any attempt to unify Taiwan and China by force will lead to a nuclear response. With this posture Taiwan would improve its ability to use asymmetric escalation to deter by denial—using nuclear weapons to deny the aggressors military objectives—and deterrence by punishment.

Had Taiwan been able to reveal an asymmetric escalation posture in the mid-1990s, would it have improved the balance of military power, sustained the status quo, and created a more stable security environment? There is no doubt Taiwan could inflict damage and deter a rational actor. Would it have been enough to deter China, who equated its national destiny with unification, including by force? Alternatively, would the revelation of Taiwan’s nuclear program intensify the cross-strait security dilemma by accelerating China’s own potential nuclear expansion? The unknowns of China’s decision calculus perplex even the modern analyst.

If the United States afforded Taiwan the space to develop a nuclear arsenal, would that have absolved America from any security commitments? One might argue the United States may have become more entangled in containing proliferation and a potential cross-strait nuclear war.

Certainly, the Republic of Korea (ROK) would not have appreciated another neighbor obtaining nuclear weapons while it faced its own nuclear-armed adversary. And Japan, given its tenuous history in the region, would likely have been unhappy to see the ROK field nuclear weapons without achieving its own equitable defense.

The discussion of alternative history matters in 2025 because middle states have witnessed what happened with Ukraine—a country without indigenous nuclear capability nor under the umbrella of protection from a third-party patron. Middle states across the world are recognizing that the security guarantees of a nuclear power extend only as far as its national interests.

It is no wonder that Ukraine now seeks a stronger security guarantee in the form of either “nukes or NATO.” And by extension, it’s not surprising that other middle states in comparable situations, like Taiwan, would re-evaluate their trust and confidence in the United States’ security promises. They see the writing on the wall with waning political interest and resources to combat adversaries in a multi-polar world.

Graham Allison observed that the United Kingdom learned, in the late nineteenth-century, rising German, Russian, French, and American navies meant its “two power standard” for naval supremacy was no longer a viable security formula without over-extending its resources. A century later, the United States finds itself in the position of Britain, compelled to re-evaluate its policies as a multipolar world challenges American dominance.

Chief among these policies must be exploring an international security strategy that defines and is faithful to American national security priorities, within available resources, unambiguous, and exploits the broad array of instruments of power. The nation must avoid the mistake of treating everything as a national security priority, rendering nothing a priority. This results in under-resourced and under-supported engagements, which erodes trust and confidence in the United States.

There will be winners and losers if the United States strikes a truly prioritized strategy. But Thucydides argues that this is the nature of international politics, however unfortunate; the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. However, as the alternative history above suggests, left to their own devices, vulnerable middle states may lean towards obtaining their own nuclear weapons. Thus, creative new security solutions must replace resource-intensive extended deterrence in those cases, if nuclear non-proliferation remains a top national security priority.

Kira Coffey is a 2024 Air Force National Defense Fellow and International Security Program Research Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center. She is a graduated squadron commander, combat pilot, and China Foreign Area Officer. Her research focuses on Great Power Competition with the People’s Republic of China.

Ryan Fitzgerald is a 2024 National Defense Fellow and Security Studies Program Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is a graduated squadron commander and combat pilot. His research focuses on International Relations and Nuclear Deterrence.

Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency.