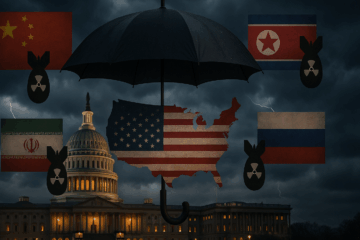

The West is behind in rebuilding the infrastructure needed to meet the emerging threats posed by China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. The re-emergence of great-power competition requires an intense effort to rebuild atrophied capabilities. The Strategic Posture Review made the case for urgent investment in modernized strategic forces including a less vulnerable road-mobile Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and expressed concern that the nuclear bomber force is currently located at only three bases with ICBMs and ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) each at two additional bases.

As the B-21 bomber enters the Air Force inventory the number of nuclear-capable bomber bases sees very little change. With the nation preparing for the geopolitical era ahead, it is time to discuss the re-commissioning of Cold War–era United States Air Force (USAF) bases, whose geographic positions can once again play an important role in deterring the axis of autocracy that is forming in opposition to American and Western leadership.

The changing strategic landscape and re-emergence of great-power competition should prompt discussion of renewing a committed focus towards strategic deterrence and the nuclear capabilities needed to deter China, North Korea, and Russia. Many Cold War–era bases were strategically located to project power and respond to threats. Re-commissioning these bases could provide needed dispersal for a bomber force that is located at only three bases. While upgrades and modernization are necessary, existing infrastructure at bases that remain in use by National Guard units, for example, or other organizations could significantly reduce the cost and time required to build a more resilient bomber leg of the nuclear triad. Tankers and other supporting components to the bomber mission would also benefit.

Utilizing existing bases could minimize environmental impacts, construction costs, and impact on local communities. While the Base Realignment and Closure effort that followed the Cold War’s end allowed the United States to reduce defense spending through dramatic cuts to infrastructure, the three-decade hiatus from great-power competition is over and the consolidation impacted deployability and introduced strategic force vulnerabilities. Today’s accelerating threat requires the urgent re-establishment of a ready network of dispersal and forward bases.

In tandem with re-commissioning Cold War–era Air Force bases, the strategic value of the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) must also be considered. As a critical asset in ensuring energy security, the SPR provides a buffer against potential disruptions in oil supply that could arise from geopolitical tensions or conflicts. Ensuring that military operations are not hampered by fuel shortages is paramount, especially when considering the logistical demands of dispersed air bases. By maintaining and potentially expanding the SPR, the US can safeguard its military readiness and resilience, ensuring that energy constraints do not undermine strategic deterrence and defense capabilities.

The expansion of the American strategic nuclear arsenal—including increasing the number of SSBNs, making Sentinel road-mobile, and acquiring more than the planned 100 B-21 stealth bombers, which are all required in the current strategic environment—underscores the need for re-commissioned bases. Not only are these bases useful for dispersal of bombers, but they have the potential to offer areas from which road-mobile ICBMs can disperse.

Admittedly, significant investment is required to modernize shuddered bases, including upgrades to runways, hangars, communication systems, and security. Environmental assessments and remediation efforts may also be necessary to address potential contamination from previous operations, adding to the cost and timeline. Re-commissioning could also disrupt local communities and raise concerns about noise pollution, safety, and environmental impacts, necessitating careful planning and community engagement. However, many towns devastated by the closure of bases would gladly welcome their return.

Significant resources are required to refurbish or rebuild facilities, integrate new aircraft and technology with existing infrastructure, coordinate with local authorities, and establish new supply chains and support networks. Legacy infrastructure at Air National Guard bases, for example, can reduce the cost and time required to build a more resilient force structure while reducing costs. ICBMs, tankers, and other support elements would also benefit.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military employed a dispersal strategy to mitigate the risk of concentrated attacks on its airbases, scattering aircraft across multiple locations to enhance survivability and ensure retaliatory capabilities. This approach was vital in countering the Soviet threat—reducing the vulnerability of strategic assets. In today’s context of renewed great-power competition, with rising threats from China, North Korea, and Russia, adjusting the current strategy is essential.

Ultimately, the decision to expand the basing footprint should be built on a comprehensive analysis of costs and benefits and a thorough understanding of strategic implications. By carefully weighing these factors, policymakers can make informed decisions that enhance national security while minimizing negative impacts on communities and the environment.

Joshua Thibert is a Contributing Senior Analyst at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies (NIDS) with nearly 30 years of comprehensive expertise. His background encompasses roles as a former counterintelligence special agent within the Department of Defense and as a practitioner in compliance, security, and risk management in the private sector. Views express are his own.

About the Author

Joshua Thibert

Joshua Thibert is a Contributing Senior Analyst at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies (NIDS)with over 30 years of comprehensive expertise, his background encompasses roles as a former counterintelligence special agent within the Department of Defense and as a practitioner in compliance, security, and risk management in the private sector. His extensive academic and practitioner experience spans strategic intelligence, multiple domains within defense and strategic studies, and critical infrastructure protection.

Iwo Jima is halfway between Guam and Taiwan.

Is there any consideration of Japan, whether alone or with others, of rebuilding the airfields?

Hi James and thanks for the great question. In my opinion, I think Japan is making it clear that they are changing their strategy military posture in response to the growing threats from China and North Korea (https://apnews.com/article/japan-us-military-command-missile-china-4e97f4cb01cfef7b6db8fb1a5df771e4). Currently, I haven’t obtained information that suggest Japan will lead efforts to recommission older airfields in the Asia-Pacific region and it seems more likely that Japan will encourage the US to expand military presence and capabilities at active airbases hosted by Japan. The US has made some early strides towards this overall objective by recently announcing the conversion of US Forces – Japan into a war fighting command which will report directly to the US Indo-Pacific Command (https://www.defenseone.com/policy/2024/07/us-forces-japan-be-upgraded-warfighting-command/398386/). Additionally, the US is increasing available air power and advanced aviation capabilities based throughout Japan (https://breakingdefense.com/2024/07/f-15ex-f-35-headed-to-japan-under-new-dod-tactical-aircraft-laydown/), and Japan recently achieved some critical military manufacturing milestones when it was recently announced that Japan had completed its first local produced F-35 (https://www.dcma.mil/News/Article-View/Article/1209525/first-japan-built-f-35-prepares-for-take-off/), and the start-up of AMRAMM and PAC-3 production (https://www.airandspaceforces.com/japan-steps-up-missile-production-in-deal-with-u-s/). Thanks again for the question and please ask more if I missed the mark in this response.

Josh – great article and it certainly opens the door for a broader discussion of reconstitution of our global power projection infrastructure and our ability to deter and defeat adversaries. In 1997 the Air Force think tank did a year long analysis of this question as it pertained to the “anti-access threat in the Southeast Pacific/China.

Bottomline – there are opportunities in the region to reconstitute and build the infrastructure required to operate in the area. In general there is a shortage of airfields that can support shorter range jets and logistics. The Chinese have spent 30 years making those that do exist more vulnerable or taken them off the board politically.

The Pentagon knew the problem existed, studied it, quantified it, identified required corrective actions, strategies and costs. Then we gutted the long range bomber force, ignored the inability of Carrier groups to generate volume or get close enough to the fight and stuck our collective head in the sand for 25 years.