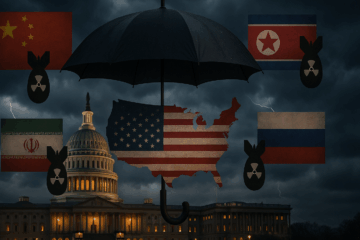

On a 2015 official visit to the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) National University of Defense Technology in Changsha, China, I (Adam) was talking with a senior PLA colonel about Chinese and American views on nuclear deterrence. The colonel, who knew I specialized in China’s nuclear weapons program, also knew that I was in charge of the United States Air Force’s professional journals Strategic Studies Quarterly and Air & Space Power Journal (Arabic, English, French, Mandarin, Portuguese, and Spanish). At one point in our conversation, the colonel looked at me and said, “I read your journal. We can match your technology, but we cannot match the quality of your officers. They are much better thinkers than our own.”

I was taken aback by his comment. It also convinced me of the role Air & Space Power Journal played, albeit small, in deterring the Chinese from choosing conflict with the United States. In the decade since that encounter, Air & Space Power Journal—Mandarin, which published Mandarin language (often translated from English) articles written specifically for a Chinese audience, ceased publication. Arabic and French editions are also no longer published. Air University Press, which publishes books by military and civilian authors and the Air Force’s professional journals, also lost several of its staff positions.

If Air Education and Training Command’s proposed 2025 budget remains unchanged, Air University Press’s operating budget will shrink to a point that operations will become virtually untenable. The circumstances are similar for National Defense University Press, which publishes Joint Force Quarterly (JFQ), and a number of books and research monographs on topics related to joint operations. Naval War College Press, Army War College Press, Marine Corps University Press and Joint Special Operations University Press also saw their budgets decline over the past decade. It is only Army University Press at Fort Leavenworth that still seems to maintain significant support—despite being smaller than at past points in time.

The decision to further reduce military press budgets in fiscal year 2025 to the point that even operating is a challenge, is short sighted in the extreme. For example, the 2025 NDU Press budget, proposed as an unfunded requirement (UFR), is 54 percent less than the 2012 budget. NDU eliminated funding for NDU Press, including Prism and JFQ, as of FY21. Temporary funds were identified, but those will likely expire in 2025. Without the UFR, NDU Press, now down to a staff of 5, will cease production of JFQ for the first time in 32 years.

Military presses play a vital role in the life of the services and the joint community. They are unique tools that allow each service to discuss and debate tactical, operational, and strategic issues internally and share and debate the perspectives of service members with the academic community, other services, allies, and partners, and, as our experiences illustrates, America’s adversaries.

For less than 0.000025 percent of the defense budget (roughly $20-25 million), the services can fully fund all seven presses. Such a sum does not even constitute noticeable waste in the federal government. Service presses play an important role that goes well beyond the few points offered above. Let us explain.

The Service Press

Just over 40 years ago, noted civil-military scholar Sam Sarkesian observed, “All militaries must be socialized into reinforcing their commitment to the political system and in their understanding of the political-social dimensions of their role as soldiers. How well this is accomplished is primarily a function of military professionalism.” The US military, as a group of individuals with specialized knowledge, “are granted autonomy contingent on maintaining the trust of the society they serve,” and in which members become experts on this knowledge and “share a commitment to common values and ethical principles.”

Debate and discussion about these issues often take place in the pages of service journals. For example, in the Spring 2024 issue of the US Air Force’s, Aether: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower, three Air Force officers discuss the challenge of “moral injury” as a result of waging war. Service presses also frequently publish articles or books on professional ethics, leadership, and related topics. They serve as a vital outlet for members of the military and civil service to identify and discuss the very challenges that undermine the character of a free nation’s military.

The importance of thinking about larger ideas and crafting thoughtful arguments is nothing new. In an October 1946 speech to the US Air Force’s Air University, Army Air Forces Major General F. L. Anderson noted, “It is not enough for airmen to be technicians. They must be versed in human affairs; they must understand the political, social, and economic aspects of international relations. They must be educated to the standard required by the history-changing role of Air Power.” Service presses serve as leading indicators of the intellectual health of the military as they affirm, explore, and expand the “specialized knowledge” of the profession as well as the all-volunteer force’s shared “commitment” to broader societal values and principles.

By providing a platform for Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, and Guardians to discuss and debate the profession of arms in a rigorous manner—a platform that includes inputs from the public at large including taxpayers, Allies, partners, diplomats, and civilian researchers—largely unavailable anywhere else, servicemembers are compelled to think deeply about war and its consequences. Consider the persistent debate over the role of retired senior military officers in US foreign policy in the pages of Parameters first in 2006 and revived again in 2020, or the Gian Gentile-John Nagl debate over Afghanistan in pages of JFQ. These professional academic fora provide an opportunity for military professionals and civilian contributors to challenge the existing orthodoxy and offer new and better approaches for achieving American interests through military means. Publications of publicly funded professional military presses are often a place for self-examination and criticism of the system. As discussed below, they are the one place where authors are free to challenge the institution they serve.

These long-standing institutions are places where the military’s best and brightest can engage with and participate in the intellectual development of the military profession and its members. In fact, key service doctrinal innovations were developed and honed in military publications—consider Air Force Colonel John A. Warden’s Five Rings, Army General Don Starry’s AirLand Battle, and Air Force Lieutenant Colonel John Boyd’s OODA Loop. Finally, professional military presses serve as a critical repository and history of the military’s intellectual development, providing Americans a window into the proclivities, trends, and concerns of a subordinate military, which, while representing a fraction of the population that the Constitution makes subordinate to civilian authority. Sadly, in an era focused on technological solutions to all military challenges, service presses and their role in encouraging innovative thought within the military is seen as expendable.

Scholarly For a Reason

Except for National Defense University Press and Joint Special Operations University Press, which work for the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and Special Operations Command, respectively, military presses are subordinate to each services’ education and training command and aligned under their professional military education institutions. These schools are civilian-accredited masters- and, in some cases, doctoral-degree granting institutions. These presses adhere strictly to civilian academic publishing standards but vary in one important way. They provide an unmatched level of support to the many military officers who seek to publish an article, book, or monograph related to their profession. Military press editors spend far more time helping their writers craft quality articles than traditional academic presses. After all, military presses serve the profession of arms, along with university academics who write for a living.

The founding of military presses and their publications date back seven decades or more. Importantly, they offer military members a place to publish that maintains a strong tradition of discourse and academic freedom. In the inaugural issue of Air University Quarterly Review in March 1947, the editorial board noted the now-familiar disclaimer that accompanies all publications of military presses, that the content therein represents authors’ opinions and may not “coincide with” that of the military service or department.

The 1947 opening statement said, “The Editor and Editorial Board wish to encourage new thinking. Consequently, if the appearance here of articles which may not agree with accepted policy, or even with majority opinion, will stimulate discussion and provoke controversy, an important part of this journal’s mission will have been accomplished: to induce airmen to have original thoughts on these matters and to give these thoughts expression.” In the immediate post-World War II era, leaders of the Army Air Forces knew how important it was to encourage airmen to think, write, and develop ideas that challenge the status quo.

Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell, established Joint Forces Quarterly in 1993, soon after the Gulf War, admonishing readers not to “read the pages that follow if you are looking for the establishment point of view or the conventional wisdom. Pick up JFQ for controversy, debate, new ideas, and fresh insights—for the cool yet lively interplay among some of the finest minds committed to the professional of arms.”

Military presses are not part of a service’s public affairs office, nor should they be. Understandably, contributions to military presses must be cleared to ensure no classified information is released and that a service’s doctrine is not misrepresented. However, well-reasoned dissent and criticism are not only acceptable but highly desired. In fact, in many cases, that is the purview of a military press—loyal opposition. Starving military presses of funding or killing them outright shuts down the very discussion they were designed to facilitate.

Contributions to military presses are necessarily wide-ranging and include everything from the fine details of drone technology to satellite operations, international political economy, deterrence, and discussions of social issues affecting the military. Again, the military not only must execute America’s political will with lethal force but must continually replenish its all-volunteer ranks through enticing individuals and families to serve.

Society-Wide Intellectual Engagement

Military presses engage in a dialogue that is both internal to each service, where iron sharpens iron, and external, where Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, and Guardians attempt to shape perspectives nationally and abroad. The relatively few academic journals that cover “security studies” broadly speaking, rarely publish the type of scholarly yet professionally focused articles and books that are the purview of service presses. This means that without them, the debate ceases to occur.

Western militaries are bureaucratic and technocratic in nature and rigorously examine failures. Coming from open societies, they often freely discuss their challenges to find the best solutions. Cutting off that discussion by killing the venues where those discussions take place will inevitably lead to suboptimal outcomes. The civilian and military contributors to service press publications, together with readers, create a larger intellectual common where dialogue that is critical to stewarding the effective execution of politics by other means takes place.

The common created by this dialogue has significant worldwide reach and impact. For example, Air University Press’s four journals have an annual audience of well over one million readers globally. National Defense University’s Joint Force Quarterly had close to one million readers worldwide in 2023. The other military presses have similar annual readerships. Ally and partner militaries read American military publications and often adopt similar thinking and approaches. Adversary militaries read American military publications and are impressed by the level of creativity, intelligence, and thoughtfulness of the United States’ military establishment.

Historical Record

Finally, military presses are an unrivaled record of military thought and the change in thinking that follows the nation’s many conflicts. Military Review is a case in point. It was first published in 1922 as a response to American involvement in World War I. In the century since the journal began, Military Review has played a vital role in the various reform movements that changed the Army after major conflicts like Vietnam, for example.

The flagship journal of the Air Force, currently represented by the journals Æther: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower and Air & Space Operations Review, turned 77 in March 2024 and predate the establishment of the US Air Force. Airpower’s evolution and debates surrounding topics like the Air Force role in countering a rising China and nuclear modernization are found in their pages.

Naval War College Review was founded in 1948 and serves as the central venue for the discussion of seapower. The journal’s archives are the central repository for discussion and debate concerning seapower’s role during the Cold War, for example.

Parameters: A Journal of Strategic Landpower published its first issue in 1971 and was largely a response to the US Army’s performance in Vietnam. Many of the post-Vietnam reforms undertaken by the Army were first discussed in its pages.

Further, these publications are peppered with the articles of field grade officers who later became general and flag officers—a sign of the importance the military places on the intellectual development of its future leaders. Just to name a few, then-Major David H. Petraeus, then-Major Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., then-Captain James Stavridis, and then-Lieutenant Colonel B. Chance Saltzman all wrote in their respective professional journals. Leading civilian scholars of the military also contribute to service professional journals. Barbara Tuchman, Richard Betts, John Mearshimer, Robert Pape, Eliot Cohen, Colin Gray, Tammi Biddle, Williamson Murray, Matthew Kroenig, and Hal Brands all contributed to the various professional publications of the military presses.

Whether Civilian or Military Outlet

Some ask why civilian-operated military-focused outlets cannot do the job of a military press. Indeed, fine civilian and association journals, such as Air & Space Forces Magazine, Texas National Security Review, Global Security Review, Marine Corps Gazette, Proceedings, Armed Forces & Society, RUSI Journal, and War on the Rocks are actively engaged in the various and important debates that arise from the military profession. However, service presses do not report to a board of directors, individual donors, or other private entities. They are publicly funded, open access, and are often staffed and led by active-duty, retired, or former servicemember with deep service-specific knowledge. This approach to publishing allows service presses to publish on topics that are important to their service, but not necessarily commercially viable.

The End of Service Presses?

For senior service leaders looking to pinch every last penny to fund new weapons or additional operations, this makes a support entity like a press an attractive target. This is a short-sighted effort to save very little money. In the case of the Air Force, eliminating Air University Press will save about $1 million in operations costs and $2 million in staff salaries and benefits. This, in an Air Force Budget of about $217 billion.

The services and the Department of Defense should reconsider the regular cuts to military press budgets. Rather than severely underfunding or effectively defunding their presses, the services and the Department of Defense should fund them to a level that allows each to perform the functions discussed above.

Service leaders must be fully cognizant of the role their presses play and the audience they serve. While most fall under the organization of each service’s military university or war college, service presses draw contributors and readers from across the service and beyond. Over 99 percent of the more than 1 million readers that learn from the Air Force’s professional journals are not students at Air University, for example.

It is also time to put to rest the incorrect belief that military presses exist solely to serve students at the various command and staff and war colleges. They do not. Instead, they belong to their respective services and provide information and research for audiences—military and civilian—at home and abroad. As such, it is perhaps time for service secretaries and chiefs of staff to take a role in ensuring that their presses continue to serve as the place where the service expresses its intellectual history, innovation, and thought.

Regardless of whether the United States wins or loses its wars, military presses and the professional books, monographs, and journals they publish will serve as the place where Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, Guardians, and members of the broader society think, discuss, and debate the profession of arms. The demise of service presses is not in the interest of any service, but it seems it will take a senior leader or Congress to step in and stop this from happening.

Dr. Laura Thurston-Goodroe is the editor of Æther and Air & Space Operations Review. Dr. Adam Lowther is the Vice President of Research at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies. The views expressed are their own.

About the Author

Adam Lowther

Dr. Adam Lowther is Vice President of Research at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies. Read the full bio here.