In the aftermath of President-elect Donald J. Trump’s election, it is time for the national political dialogue to calm down and move away from dysfunctional hyperbole. During the presidential campaign, political activists and media commentators trafficked in exaggerations and misrepresentations of facts that distracted from responsible debates on public policy. Admittedly, some of this political blather is simply risible on its face and can easily be dismissed by attentive voters. But other examples of misspoken or written malfeasance are more serious.

One example of this malfeasance was the repeated use of the term fascism/fascist or Nazism/Nazi to refer to Donald J. Trump and his supporters. Among those raising this concern were disaffected officials from the first Trump presidency. For example, retired four-star general John F. Kelly, who served as Trump’s White House chief of staff, caught media attention by going public with warnings that Trump would try to govern as a dictator.

In addition, thirteen republicans who served in the first Trump administration released an open letter on October 25 charging that Trump’s disdain for the professional military and his admiration for autocrats would be dangerous for America. They contended, “The American people deserve a leader who won’t threaten to turn armed troops against them, won’t put his quest for power above their needs, and doesn’t idealize the likes of Adolf Hitler.”

The widespread use of the fascist moniker by Trump opponents, as well as the identification of Trump as an admirer of Hitler, substitutes emotional frustration for a nuanced appreciation of history and policy. This is so for at least two reasons.

First, the Nazi and fascist ideologies of the 1920s and 1930s cannot be replicated in 21st- century America. There are too many checks and balances in the American system of government to permit a fascist dictatorship or a similarly authoritarian system from taking root in the United States.

The geniuses who designed the American system of government dispersed power among three branches of the federal government and divided powers between the federal government and the states for a reason. The priority of values in the American political system favors liberty over efficiency. Admittedly the apparent inefficiency of government compared, say, to private business, is sometimes frustrating. But Americans instinctively mistrust centralized power as inimical to freedom, and history validates the prudence of that judgment.

Second, the character and training of the US professional officer corps would preclude the collaboration of the highest-ranking generals and admirals in subverting democracy. The graduates of American war colleges are steeped in the constitutional legitimacy that surrounds civil-military relations. An anti-democratic usurper demanding that the armed forces become partisan subordinates, as opposed to apolitical guardians of democracy, would meet with Pentagon resistance and, if necessary, refusal to carry out illegal orders.

Of course, complacency on the character of civil-military relations is never desirable; democracy must always be safeguarded against imminent dangers. But overstatement of American vulnerability to any single president or administration is distracting from more probable and immediate dangers and challenges.

First among these dangers is the relentless march of technology and its tendency to produce an elite of technocrats who exert indirect or direct control over public choice. When technocrats are in the private sector, they can influence public policy indirectly by leading successful corporations that make desirable consumer goods or other commodities.

On the other hand, when technocrats reside in government bureaucracies, their influence and power are not determined by market forces, but by law and government regulation. For most of the 20th century, the United States successfully balanced the creativity of the private business sector with the regulatory regimes of government bureaucracy. In the twenty-first century, this balance is at risk by bureaucracy in hyperdrive.

Aided by the explosion in new information technology, the federal bureaucracy now resembles Cheops’ pyramid and intrudes into every corner of American life. In turn, a more activist government is demanded by disgruntled interest groups or litigious citizens who take every grievance, real or imagined, into the local, state, or federal judicial system.

The result is a logjam of jurisprudential clutter and a never-ending cascade of regulations that dictate how Americans work, eat, sleep, drive, watch television, cook, and educate their children. A list of things that the government does not regulate would be harder to draw up than a list of things that the government controls directly or indirectly.

In short, mastery of advanced technology is a necessary condition for American national security and defense. On the other hand, technological micro-management of the American body politic can only depress innovation, discourage original thinking, and empower dysfunctional government controls over social and political life.

A second concern that both political parties need to address is the restructuring of the international political and economic system to the detriment of American leadership and security. Russian President Vladimir Putin recently hosted a conclave of member states of BRICS (originally Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) plus some thirty other countries interested in joining or otherwise supporting the group. BRICS is explicitly designed to push back against the rules-based international order led by the US and its Western allies.

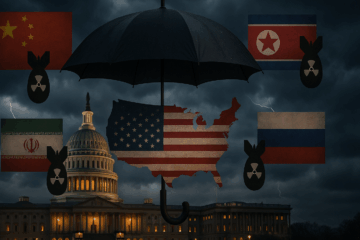

On the international security front, China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea (the CRINKs) are acting in concert as system disrupters in support of aggression in Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia. Iran and North Korea are providing explicit military assistance to Russia for its war against Ukraine, including ballistic missiles and drones.

North Korea has also begun sending troops to fight under Russian command in Ukraine. China has moved into a more open military alliance with Russia, that includes joint war games and training exercises, including scenarios with forces that are potentially nuclear-capable. Russia is confident that it can outlast Ukraine in manpower and war-related resources despite NATO support for Kiev. At the level of high diplomacy and statecraft, no recipe for a negotiated settlement of this war is on offer.

China continues to press forward its Belt and Road Initiative and other measures to dominate global trade and infrastructure development. As well, China apparently aspires to become a third global nuclear superpower, with forces essentially equivalent to those of the United States and Russia by 2035 or sooner.

A third concern that should occupy the attention of the next administration is the matrix of challenges to American and allied conventional and nuclear deterrence. Russia’s war against Ukraine, China’s gathering storm for a future strike against Taiwan, and Iran’s wars against Israel via proxies in Gaza, Lebanon, and Yemen, all point to a decline in respect for American power and a willingness to test American resolve by direct or indirect action.

In addition, Iran is already a threshold nuclear weapons state, and an Iranian bomb could set off a reaction among Middle Eastern countries that would make a serious dent in the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Iran’s Houthi proxies in Yemen have diverted maritime commerce throughout the world and have evolved from a fledgling insurgency into a well-armed terrorist strike force capable of ballistic missile and drone attacks throughout the region.

With respect to nuclear deterrence, the fate of the American strategic nuclear modernization program that was supported by the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations is now uncertain as to its timing and continuing support from Congress. The intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) component (Sentinel) of the nuclear triad faces scrutiny over its rising costs and delayed schedules. The possible collapse of the New START regime in 2026 could presage an open-ended nuclear arms race among China, Russia, and the US.

Other challenges to nuclear deterrence stability include developments in hypersonic offensive weapons, in advanced missile and air defenses, and in space and cyber weapons for deterrence or defense. Kinetic attacks on US space-based assets and cyberattacks against both military and civilian targets can be acts of aggression in themselves; or, on the other hand, they can be precursors for nuclear first strikes or for large-scale conventional offensives against American and allied North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) forces and infrastructure.

In short, (1) managing the balance between governmental and private-sector technology innovation; (2) steering the pivotal role of the United States in a more competitive international system; and (3) supporting credible conventional and nuclear deterrence against more ambitious regional actors and nuclear competitors provides a partial menu of priorities that should receive more attention from policymakers. Demagoguery’s day has passed. It is now time to govern for the betterment of the nation.

Stephen Cimbala, PhD, is a senior fellow at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies and Professor of Political Science at Penn State Brandywine.

About the Author

Stephen Cimbala

Dr. Stephen Cimbala is Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Penn State university, Brandywine. He is currently a senior fellow with the National Institute for Deterrence Studies.

I agree wholeheartedly with Steve. There is more than enough divisive misinformation coming at us from America’s foreign adversaries. It is high time for all parties and persons in the USA to come together, to prevail in the extremely dangerous Cold War II now being forced on this country and our allies by the CRINKs. Let us more forward together with unity!