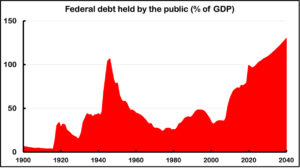

The United States government finds itself in an unprecedented financial situation. Over the next 12 months, the amount of public debt held by the federal government will exceed the size of the nation’s economy. As a fraction of gross domestic product (GDP), debt has grown to a size not seen since the end of World War II. Projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicate debt will continue to grow to 130 percent of GDP by 2040.

Data source: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59710#data

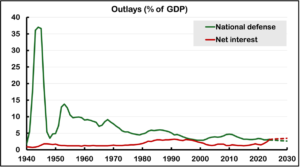

Deficit spending is a long-standing tradition in the US, with a budget surplus occurring in only four of the past 50 years. Debates about the size and importance of the federal debt raged for decades. With interest rates at historically low levels prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, debt financing came at a relatively small price soothing many concerns about deficit spending. Over the 2010s, net interest to finance the debt averaged only 6.8 percent of government spending and just 1.4 percent of GDP. Low interest rates led some to argue that “[t]he economics of deficits have changed,” and that reducing the debt and deficit spending should be a low priority compared to continued government investments in security, infrastructure, and well-being.

Two fundamental factors emerged to accelerate debt accumulation during the COVID-19 pandemic and aftermath. First, federal deficit spending limited the negative economic consequences of federal, state, and local responses to COVID-19. Second, the Federal Reserve sought to control inflation, a result of the Federal Reserve’s practice of “quantitative easing,” by increasing interest rates following the end of the pandemic—increasing government borrowing costs. The overall result was that net interest on government debt more than doubled between 2019 and 2024 in actual dollars. More funds spent to finance the debt leaves a smaller fraction of outlays available for discretionary spending, including national defense.

Data source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59710#data

As the above chart illustrates, the percentage of GDP allocated to debt repayment surpassed defense spending in 2024. Future CBO projections appear in dashed lines. Major wars in Korea, Vietnam, and the height of the Cold War increased defense spending in the short term, but the overall trend was downward. Future defense spending is increasingly constrained by spending growth in both debt and nondiscretionary programs. With debt repayment exceeding defense spending, the American people should see this as a warning that must be redressed. Given great-power competition with China and several active hotspots around the world, decreasing American defense funding as a fraction of GDP is a significant concern. However, defense spending remains at a relative high point when examined in constant-year dollars.

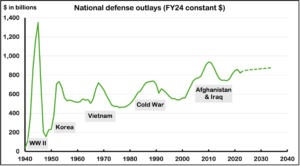

Data source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59710#data.

The size of defense budgets, accounting for inflation, provides a more optimistic view. The solid line presents historic defense spending in constant 2024 dollars and the dashed line, again, represents CBO projections. From 1950–2000, US defense spending increased significantly during major conflicts and at the height of the Cold War. Over those fifty years, peaks in defense spending remained below $750 billion in fiscal year 2024 dollars. Post–September 11, 2001, operations resulted in much higher levels of spending, approaching $940 billion at its peak. Even with reductions over the 2010s, spending over the next decade projects to be 15 percent higher annually than at the peak of the Cold War.

Even with high levels of spending, the current US force structure is in desperate need of modernization due to a laser-sharp focus on counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations in prior decades. Since the year 2000, operations and maintenance (O&M) spending has taken an increasing share of the national security budget. This means the United States is using its assets in combat and on deployment. Over the past 24 years, O&M averaged 39 percent of the national security budget. In the 35 years prior to 2000, this number was only 30 percent.

The growing fraction of O&M costs left a smaller fraction of the budget available for system acquisition. What funds remained were heavily focused on winning the Global War on Terrorism, meaning that investments in technologically advanced systems to counter threats posed by China and Russia often took a back seat. A second effect of the lack of procurement is that today’s military is simply smaller. For example, the US Air Force will soon have a fleet of less than 5,000 aircraft for the first time in its history and the US Navy will sail only half the ships it did 40 years ago. The outcome of these decisions, according to leading researchers, is that the “US defense strategy and posture have become insolvent.”

What does this situation mean for the security of the US and its allies? While American involvement in a major conflict would certainly result in increased defense spending, there is precious little room for the peacetime defense budget to grow without large tax increases or significantly reduced spending on entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare. The most likely outcome is that new investments will need to come at the expense of other platforms or spending inside the defense budget.

Closing the gap between strategic goals and the means needed to achieve those goals during this dangerous time of strategic competition requires a thorough examination of solutions beyond increasing defense spending. The defense strategy needs rightsizing and a focus on the most stressing threats to the nation’s security. New concepts for imposing costs on competitors need to be developed. Methods to deter conventional and nuclear conflict should also be prioritized with special attention paid toward developing methods to prevent a conventional conflict from escalating across the nuclear threshold.

Carl Rhodes, PhD, is a Senior Fellow with the National Institute for Deterrence Studies and the founder of Canberra-based Robust Policy.