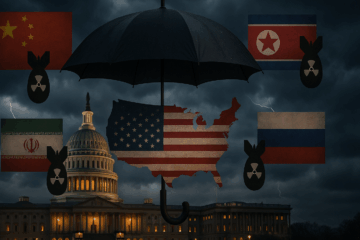

North Korea’s rapid advancements in nuclear miniaturization, missile technology, and multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV) capabilities are accelerating the risk of nuclear decoupling among the US, Japan, and South Korea—undermining the credibility of deterrence in the region. Given this grave security challenge, what realistic measures can be taken to prevent nuclear decoupling?

Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK), as key American allies, should strengthen their conventional military capabilities, both offensive and defensive, to reinforce regional deterrence. Two critical steps are needed. First, Japan and South Korea must expand their capabilities to neutralize North Korea’s missile launchers. Second, Japan’s defense architecture should be aligned with South Korea’s Three-Axis System to create an integrated deterrence framework.

So far, to address concerns over potential nuclear decoupling, the US, Japan, and South Korea have explored multiple options. In addition to Washington’s repeated assurances that its nuclear extended deterrence remains intact, discussions have included modernizing American nuclear weapons, expanding nuclear-sharing agreements, redeploying tactical nuclear weapons to South Korea, and even the possibility of South Korea developing its own nuclear arsenal.

However, South Korea acquiring nuclear weapons remains highly improbable due to its significant political costs. From the 1960s to the 1980s, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) member-states feared the US might hesitate to retaliate with nuclear weapons if the Soviet Union launched a nuclear strike on Europe. While NATO pursued multiple strategies—most notably the dual-key system and the deployment of Pershing II missiles—these measures never fully resolved nuclear decoupling concerns.

Ultimately, NATO never confronted the full extent of this dilemma as the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Since the issue lies not in the US’s ability to retaliate but in its willingness to do so under specific conditions, the most practical approach is to adopt deterrence measures that North Korea perceives as credible.

First, Japan and South Korea should prioritize expanding their capabilities to neutralize North Korea’s nuclear missile launchers. A key advantage for the US, Japan, and South Korea—compared to NATO during the Cold War—is that North Korea is estimated to have around 50 nuclear warheads, far fewer than the tens of thousands in the Soviet arsenal.

In this context, Japan’s planned acquisition of enemy base strike capabilities should focus not only on expanding the number of available strike assets but also on improving their precision and destructive power to ensure maximum effectiveness against North Korean launch sites. At the same time, South Korea’s kill chain should further enhance its deep-strike capabilities by increasing assets like the Hyunmoo-4 missile, which is designed to penetrate deeply buried facilities.

Additionally, South Korea’s Drone Operations Command, established in 2023, should undergo a major expansion in drone assets capable of effectively detecting, tracking, and striking North Korean missile launchers. By integrating high-precision missiles and unmanned systems, both Japan and South Korea can significantly reduce North Korea’s ability to deliver nuclear strikes, thereby reinforcing deterrence.

Second, as Japan and South Korea expand their strike capabilities, Japan’s defense architecture should be aligned with South Korea’s Three-Axis System. This integration would allow both countries to allocate their finite military assets more effectively when targeting North Korea’s nuclear-related ground units. For example, given the geographic distance, Japan could focus on striking fixed targets such as command centers and underground missile storage sites while South Korea concentrates on eliminating mobile launchers that require rapid response and precision strikes.

Additionally, harmonizing Japan and South Korea’s missile defense structures would improve the likelihood of intercepting North Korean missiles. While Japan has developed its missile defense in close coordination with the United States, South Korea has opted to develop its own independent missile defense system, instead of fully integrating into the American-led ballistic missile defense framework.

However, aligning the two countries’ missile defense systems would significantly enhance regional interception capabilities. A fully integrated defense network would not only establish a more layered interception system against incoming North Korean missiles but also enable earlier response times—as Japan and South Korea deepen their real-time missile-tracking cooperation—South Korea’s response times could improve further. By improving both offensive and defensive coordination, Japan and South Korea can maximize deterrence and reduce North Korea’s nuclear strike effectiveness.

By implementing these measures, North Korea would be left with only a limited number of launchers capable of delivering nuclear weapons. While it is possible that some missiles could still be launched from the remaining launchers and a few might evade American missile defenses, North Korea would have to consider allocating few nuclear warheads against Japan, South Korea, and the United States. This would be necessary both to achieve its long-term political objectives and to deter US-ROK combined forces and US Forces Japan (USFJ) from retaliating in the short term.

Moreover, North Korean leadership would face significant uncertainty about whether its remaining nuclear missiles could successfully penetrate American missile defenses. In essence, by increasing their conventional strike capabilities and aligning their military strategies, Japan and South Korea could ensure that a substantial number of North Korean launchers are neutralized. This would force Pyongyang to operate with significantly reduced military options, making its attempt to create nuclear decoupling less credible.

However, this strategy is only viable as long as North Korea’s nuclear arsenal remains limited. If Pyongyang dramatically expands its warhead stockpile and launch platforms, conventional deterrence alone will no longer be sufficient, and the risk of nuclear decoupling will escalate beyond control. The US, Japan, and South Korea must act decisively—before the balance of power shifts irreversibly in North Korea’s favor. Time is running out.

Dr. Ju Hyung Kim, CEO of the Security Management Institute, a defense think tank affiliated with the South Korean National Assembly, is currently adapting his doctoral dissertation, “Japan’s Security Contribution to South Korea, 1950 to 2023,” into a book.

About the Author

Ju Hyung Kim

Dr. Ju Hyung Kim, CEO of the Security Management Institute, a defense think tank affiliated with the South Korean National Assembly, is currently adapting his doctoral dissertation, “Japan’s Security Contribution to South Korea, 1950 to 2023,” into a book.