Strategic stability as it was once known is on life support. For those unfamiliar with the concept, strategic stability is a condition of strategic power balance that enables deterrence to function more effectively. The obvious goal of deterrence is conflict prevention and the attendant risks of regional and global nuclear escalation. For over 75 years this global deterrence architecture relied on a highly credible American strategic force posture, comprised of strategic and theater nuclear forces and limited homeland missile defenses.

Today, the international security environment is anything but stable, certain, and peaceful. And the future is trending in the wrong direction for the United States and its allies. American strategic force posture must be rebalanced. The US needs a policy of strategic sufficiency 2.0 with new regional nuclear triads as its centerpiece.

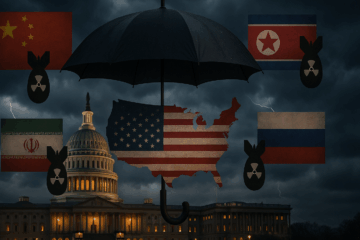

Those who favor a rules-based construct of international relations now face the specter of broad and catastrophic threats from a new axis of authoritarianism. This axis is a political union comprised of authoritarian China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia, each guilty of intense human rights abuses of their own people. They seek to create a new world order of control, coercion, and, when needed, armed conflict where they reap the benefits. This new political union could include aggression against the US and its allies simultaneously.

Their military prowess is greatly increasing, through a nuclear arms race that the United States is passively observing. Most importantly, this includes theater nuclear forces of short-, medium-, and intermediate-range missiles in the Pacific and Europe. Today, the US simply has no theater range nuclear forces forward-deployed to the Pacific. According to the Congressional Research Service, all American nonstrategic nuclear weapons are either forward-deployed with aircraft in Europe or stored in the United States. Further, with Russia possessing as many as 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear weapons in its arsenal, the US and NATO are outpaced in theater nuclear forces in Europe by perhaps a 10-to-1 margin.

Unlike the Cold War, these threats are undergirded by China’s economic power, ironically fueled for decades by liberal societies enamored with China’s cheap product and labor. It is meaningless to characterize the American relationship with these regimes as competition. The United States and its allies are in conflict with them, not yet armed conflict, but conflict, nonetheless.

The US has four broad policy choices for its strategic force posture. First, it can stay within guidance of the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) and slowly modernize the strategic nuclear triad while reducing reliance on nuclear weapons hoping adversaries follow. However, every nuclear-armed adversary is deepening reliance on nuclear weapons and expanding nuclear forces, with no signs of stopping.

Second, the US can seek an isolationist foreign policy and aid its allies in developing and deploying their own nuclear capabilities. This option requires that the US all but abandon its policy of extended deterrence and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), placing regional security in peril and fostering geopolitical atrophy.

Third, it can promote new security architectures in Europe and the Pacific, where a leading regional ally would assume responsibility for providing the needed “nuclear umbrella” over fellow regional allies. This option is likely unworkable.

The fourth option is for the US to embrace its historical leadership role, strengthen its strategic force posture, and, working with Allies, reconstitute regional conventional defenses. The last option is the only prudent one to prevent conflict through deterrence against multiple adversaries for the foreseeable future. The logic of such a strategy should start with President Richard Nixon’s approach.

In the late 1960s, Nixon formulated a realist policy of “strategic sufficiency.” It was designed to adjust the American strategic force posture to the threats, uncertainties, and instability of that time. Such threats included rapid growth in Soviet nuclear forces and the prospect of simultaneous armed conflict with multiple nuclear-armed adversaries. Nixon concluded strategic balance was essential for overall security, though it meant expanding the American nuclear forces immediately. Quantity was a quality all its own. If numbers mattered to the Soviets, then the United States needed to include them in sufficiency assessments.

In his first annual foreign policy report to Congress, Nixon argued strategic sufficiency required a military calculation of forces for warfighting, but explicitly argued sufficiency’s core idea was political. Forces could only be sufficient if they accounted for vital and long-term American security interests and aspirations, including the protection of global commercial markets.

Combined, the military and political features of Nixon’s sufficiency enabled the US strategic force posture to accomplish a wide set of policy goals. These included deterring the Soviets, assuring allies, countering coercion, providing a president political bargaining power to successfully wage an escalatory battle, fight and finish war on multiple fronts, and safeguard long-term interests.

To rebalance the force, the Nixon administration moved to upload nuclear missiles with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV) to be able to attack more targets and overcome enemy defenses without reliance on a launch-on-warning strategy. Nixon also hardened intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos, increased the mobility of forces, and increased air and missile defenses. Nixon coupled American security to allied security but demanded more of allies especially for conventional forces to deter regional aggression. Such was the logic and choices of Nixon’s policy.

However, Nixon’s sufficiency policy was formed in the 1960s, in an era when large or surprise Soviet nuclear attack was feared. It focused on American strategic nuclear forces that provide central deterrence of attacks on the homeland. Today, the most likely pathway to nuclear escalation and attacks on the homeland is through regional conflict, where adversaries have a significant and growing theater nuclear advantage, particularly in sub-intercontinental-range missiles. Allies are faced with direct and immediate threats of aggression and nuclear attacks. The United States nuclear triad of strategic systems is neither designed nor credible for waging regional nuclear war and escalation. It invites nuclear retaliation on the homeland.

Therefore, a strategic sufficiency 2.0 for the future must include nuclear forces necessary to satisfy Nixon’s military-political goals, but with a focus on the theater. Beefing up the American strategic nuclear triad is important, but so is expanding regional conventional forces and homeland defenses. However, the greatest deterrence priority for this new axis of authoritarianism is building American theater nuclear triads.

Adversaries calculate the totality of war and the risks of escalation all the way through war termination prior to making the initial decision to wage war. And so, the strategic force posture must have the forces in place to succeed at every step of conventional and nuclear war in order to deter war. Regional nuclear triads plug the greatest force sufficiency gap in this spectrum.

Regional nuclear triads would create a deterrent wall between regional conventional conflict and escalation to strategic nuclear conflict against the homeland. Today, such walls are virtually nonexistent. Regional nuclear triads in Europe and the Pacific would be sufficient to provide the president a wide range of theater options to counter simultaneous axis escalation threats, without having to move forces from one region to the other. Such diverse options enable a president to successfully wage the regional escalation battle without using the strategic triad. To use the strategic triad would pointlessly drive central deterrence risks to the homeland.

Regional nuclear triads not only build the critical deterrent wall, but they are also sufficient to accomplish, at the regional level, the full range of Nixon’s military and political features noted above (deterrence, assurance, counter-coercion, escalatory bargaining, and war winning). Theater nuclear forces of such strength also hedge against the uncertainties involved in adversary nuclear force projection and intentions in the outyears. This reduces regional and homeland risks, and builds the high confidence needed of a strategic sufficiency policy.

Regional nuclear triads would have varying ranges and yields for proportionality and credibility and would afford the same force attributes of survivability, responsiveness, and flexibility provided by the strategic triad. This combination of attributes creates the military, political, and psychological effects that maximize adversary doubts and fears of the consequences of undesired actions. Placing regional nuclear triads in Europe and the Pacific achieves this strong regional deterrent effect unlike any other policy option.

This should be achieved in both theaters. For example, the United States can deploy a combination of ground-based nuclear-armed hypersonic weapons and nuclear-armed F-35 aircraft, nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (the SLCM-N), and air-launched nuclear-armed hypersonic missiles. Regional nuclear triad means-of-delivery and nuclear weapons must also be of sufficient numerical strength to balance Russian theater nuclear forces in Europe and Chinese/North Korean theater nuclear forces in the Pacific.

As mentioned earlier, American strategic force posture must account for military and political force requirements across the spectrum of conflict. Therefore, in addition to regional nuclear triads, strategic sufficiency 2.0 also requires an American strategic force posture to make three other adjustments to deal with threats.

First, the US must upload its ICBM force with additional nuclear weapons. In keeping with Nixon’s uploading policy, the US should use uploaded missiles to keep pace, weapon for weapon, with Chinese strategic nuclear weapon deployments. This achieves the military and political purposes stated earlier, but also demonstrates political resolve toward arms control at some point.

Second, the posture must safeguard key elements of the homeland from enemy coercion. Missile defenses reassure the American people, but also enable a president to take the risks necessary to effectively escalate and win a conflict where nuclear use is threatened or takes place. A limited defense against coercive attacks against major American population centers and adversary first-strike weapons against American leadership adds that needed reassurance to the deterrence equation.

Third, in partnership with allies, the US must restore regional conventional forces to deter axis aggression. This should include a substantial number of American air-, sea-, and land-based conventional hypersonic missiles capable of defeating, at range, enemy defenses and their anti-access area-denial capabilities. It will also require greater allied burden and risk sharing through increased defense spending, expanding regional combat power and expanding access for American theater nuclear forces.

Challenges to a strategic sufficiency 2.0 policy come in several forms. Detractors may make the following arguments.

First, some may argue that expansion of American nuclear forces will spark an arms race. Unfortunately, an arms race already exists. The United States is not a participant.

Second, some may argue nuclear expansion is unaffordable. Nuclear forces, including ongoing strategic triad modernization, account for 6 percent of the defense budget and less than 1 percent of federal spending. Regional nuclear triads, uploading, conventional hypersonics, and improved missile defenses are minimal in cost. Deterrence is, however, far less expensive than warfighting.

Third, some may suggest a single nuclear weapon system, such as the submarine-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), is all that is needed for regional deterrence. But this approach leaves out critical military and political features of sufficiency such as attributes, warfighting capabilities, and escalation options that regional nuclear triads offer.

Finally, some could argue that the United States can accomplish its military and political objectives if the nation can strike key targets with the strategic nuclear triad. This force sufficiency assumption is a common trap. Nixon argued that while narrow military planning is necessary in helping to discern strategic sufficiency, he warned against “debatable calculations and assumptions regarding possible scenarios.” Rather, sufficiency dealt more with force capacity in its “broader political sense.” Anything less than full force balance is unacceptable.

The policy of the United States should be to embrace leadership and engagement in the world to resolutely safeguard its national security and that of its allies and partners. To do so, American policy should be to reconstitute strategic force posture, including expanding the strategic nuclear triad through MIRVing ICBMs; establishing theater nuclear triads in Europe and the Pacific; expanding missile defenses; and expanding theater conventional forces.

War prevention is the object of deterrence, a strategy that has worked for over 75 years. Deterrence, strategic stability, and nonproliferation were always the strongest when the US and its allies were strong. Power is the language respected by authoritarians, and the US should not be afraid to wield it. Strategic sufficiency 2.0, with an emphasis on regional nuclear triads, can rebalance the American strategic force posture and create the conditions of strategic stability and deterrence effectiveness against the multipolar axis threat.

Jonathan Trexel, PhD, is a Senior Fellow at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies and on the faculty of Missouri State University. The views presented in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of US Strategic Command, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Dr. Trexel’s thorough and cogent article is an important contribution to how to best rapidly reconstruct what POTUS Nixon called Strategic Sufficiency, which McGiffin’s and Lowther’s overall concept of “Dynamic Parity” effectively updates into the multipolar and multi-rogue realpolitik of Cold War II, now underway. Specifically, regional triads would extend America’s nuclear deterrent from strategic level at intercontinental ranges and H-bomb yields into more balanced forward deployed weaponry as well, in both Europe and Asia, with warhead yields covering the key current escalation-ladder spectrum GAP from under 100 kt “conventional” fission bombs down to parity with Russia’s “clean mini-nukes” with yields well under 1kt. This great suggestion would close a dangerous gap in the U.S.’s ability to meet and answer armed aggression at ALL levels of intensity from conventional-only through to thermonuclear — the only real way to sustain effective deterrence that most strongly avoids any such large shooting wars to begin with. Make no mistake, freedom’s adversaries look for and will exploit every chink in our armor. A serious tactical nuclear disadvantage (extreme NON-parity) in Europe, and a virtual lack of ANY low-yield nuclear forces forward deployed in Asia, is inviting impending military and peacekeeping disaster. Thank you, Dr. Trexel.