Is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) a national security organization? The answer matters greatly in the division of labor between government agencies, as well as how NASA should interpret national guidance.

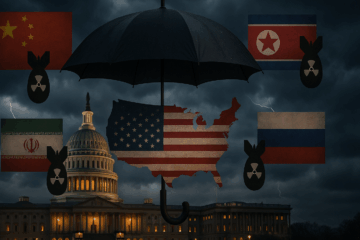

The United States’ current National Security Strategy states that an era of “strategic competition” exists, which the recent Joint Concept for Competing defines as “a persistent and long-term struggle that occurs between two or more adversaries seeking to pursue incompatible interests without necessarily engaging in armed conflict with each other.” It notes how America’s “adversaries are employing cohesive combinations of military and civil power, below the level of armed conflict, to pursue objectives that threaten the strategic interests of the United States, its allies, and its strategic partners” and to “win without fighting.”

If NASA is a national security organization, then it may be a primary, even principal tool to protect America’s strategic interests and to achieve America’s strategic objectives and should act responsibly as a custodian of America’s security interests, rather than merely as a science and exploration agency. So, is NASA a national security organization?

Many will say no and argue that NASA has a science and exploration mission, and that “NASA doesn’t do security.” Some assert that NASA was specifically created by President Eisenhower, distinct from the military industrial complex to be a tool of diplomacy, with national security belonging elsewhere.

Of course, that might come as news to President Dwight D. Eisenhower himself, who partially created NASA as a cover for his top-secret National Reconnaissance Organization (NRO). It likely would also come as a surprise to President Kennedy and to the first generation of Cold Warriors at NASA, who heeded President John F. Kennedy’s call that “the eyes of the world now look into space, to the Moon, and to the planets beyond. And we have vowed that we shall not see it governed by a hostile flag of conquest, but by a banner of freedom and peace.” They won the first great victory of the Cold War—America’s first strategic competition.

President Lyndon B. Johnson said, “control of space means control of the world.” In fact, declassified documents reveal that NASA’s Mercury, Saturn, and the Apollo Manned Lunar Landing Programs were designated as the “highest national priority category” under the Defense Production Act.

It would surprise Congress, who authorized NASA, the most. NASA’s purposes are codified in Title 51–National and Commercial Space Programs of the United States Code. The law states,

Congress declares that the general welfare and security of the United States require that adequate provision be made for…space activities. Congress further declares that such activities shall be the responsibility of, and shall be directed by, a civilian agency exercising control over…space activities sponsored by the United States, except that activities peculiar to or primarily associated with the development of weapons systems, military operations, or the defense of the United States (including the research and development necessary to make effective provision for the defense of the United States).

It also unambiguously states, “the making available to agencies directly concerned with national defense of discoveries that have military value or significance,” and that “the administration and the Department of Defense, through the president, shall advise and consult with each other on all matters within their respective jurisdictions related to…space activities and shall keep each other fully and currently informed with respect to such activities.” In fact, NASA has a long history of direct cooperation, during the Cold War, with the Air Force, DARPA, SDIO, and NRO to advance the nation’s security interests through peaceful means and applications.

NASA’s primary job during the first strategic competition was to showcase the vibrancy of democratic capitalism over the Soviet Union’s centrally planned economy. Landing a person on the Moon, a symbol for national strength, was a way to woo newly independent states to the West’s side of the Cold War.

When the Cold War ended, NASA still had a security mission, but without the broader context of strategic competition it was asked to enhance security through diplomacy. This also included employing Russian rocket scientists and engineers to prevent them from building intercontinental ballistic missiles for Iran, Iraq, and North Korea.

According to the NASA Administrator, America is in a new space race as part of a broader strategic competition with China and Russia. This time it is not using space technology as a symbolic proxy of national power, but rather developing space technology to secure long-term national economic power. Thus, NASA was given a mission to lead the “return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization.”

The national vision begins with a “campaign to utilize…the surface and resources of the Moon, and cis-lunar space to develop the critical technologies, operational capabilities, and commercial space economy.” The National Cislunar Science and Technology Strategy explains that the United States will “leverage collaborations with private entities to enable capabilities for large-scale ISRU and advanced manufacturing at the Moon.”

Despite such clear policy direction from two administrations, it is not uncommon to hear NASA personnel eschew any mandate for economic development or industrial development in space, preferring to concentrate only on what advances their own exploration. The mandate is crystal clear in law.

In Title 51, NASA’s purpose includes, “the preservation of the United States preeminent position in…space through research and technology development related to associated manufacturing processes” and the “preservation of the role of the United States as a leader in…space science and technology.” Title 51 also calls for the “establishment of long-range studies of the potential benefits to be gained from, the opportunities for, and the problems involved in the utilization of…space activities.”

NASA is a national security organization whose duties include ensuring the pre-eminence of the United States. Its job is not to build weapons or engage in conflict—but to pursue American strategic objectives below the threshold of armed conflict. Now that the US is once again in strategic competition, it is time for NASA to return to its roots as a primary competitor in seeding and cultivating economic, industrial, and logistical expansion. Thus, NASA’s Artemis planning must not be only in the narrow context of a Moon-to-Mars exploration program, but also must be made in the broader context of securing long-term economic security for the United States and its partners.

Peter Garretson is a Senior Fellow in Defense Studies at the American Foreign Policy Council (AFPC), co-director of AFPC’s Space Policy Initiative, and author of Scramble for the Skies: The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space and The Next Space Race: A Blueprint for American Primacy. The view’s expressed are the authors own.

About the Author

Peter Garretson

Peter Garretson is a Senior Fellow in Defense Studies at the American Foreign Policy Council (AFPC), co-director of AFPC’s Space Policy Initiative, and author of Scramble for the Skies: The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space and The Next Space Race: A Blueprint for American Primacy.